Reports on Plant Diseases |

RPD No. 412 - Rusts of Turfgrasses

|

June 2000

|

[ Symptoms ] [ Disease Cycle

] [ Control ]

|

All commonly grown turfgrasses in the Midwest — bluegrasses, fescues,

ryegrasses, zoysiagrasses, and bermudagrass — are attacked by one

or more rust fungi in the genus Puccinia (Table

1). Other rust genera (Uromyces and Physopella) attack

turfgrasses outside of the Midwest. Bentgrasses are usually not affected.

Rust fungi are obligate parasites and infect only living grass plants.

Two or more rusts may attack the same grass plant at the same time. Grass

plants are most easily infected under stressful growing conditions.

Rusts are most severe when water and fertility are less than adequate

for good growth. Most rust problems occur on Kentucky bluegrass, perennial

ryegrass, tall fescue, and zoysiagrass. These diseases occur throughout

the United States wherever susceptible grasses are grown.

Most rusts do not usually become a growth-limiting problem until mid

to late summer during extended, warm to hot, humid, but dry periods when

grass grows slowly or not at all and nights are cool with heavy dews.

Some cultivars of Kentucky bluegrass (such as Birka, Campus, Delft, Eclipse,

Lovegreen, Merion, Mystic, Prato, Touchdown, and Windsor), several of

the newer perennial ryegrasses (Derby, Manhattan, Pennfine, and Regal),

zoysiagrasses, Pennlawn creeping fescue, and Sunturf bermudagrass are

particularly susceptible.

|

Click on images for

larger version

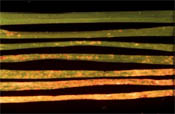

Figure 1. Leaf

rust on

bluegrass showing advancing

stages of infection.

Figure 2. Bluegrass

attacked by rust.

|

Severe rust infection causes many grass blades to turn yellow to brown, wither,

and die. Such turf may be thinned and weakened and also be more susceptible

to winter-kill, drought, weed invasion, and other diseases. Like powdery mildew,

rusts are often more serious in the shade.

|

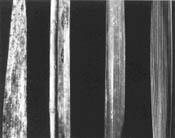

Shortly after infection, a close examination of the grass blades and

leaf sheaths will show small light yellow flecks. These soon enlarge.

In several days, the epidermis ruptures and tears away to expose the round,

oval, or elongated powdery, spore-filled pustules, which may be reddish

to chestnut brown, brownish yellow, bright orange, or lemon yellow (Figures

1 and 2).

The powdery material rubs off easily on hands, shoes, clothing, and animals.

Where severe, rust-affected leaves or even entire plants may turn yellow

(orange on zoysiagrasses), wither, and die. Severely rust-infected turf

soon takes on a reddish brown to yellowish or orange appearance, depending

on the rust involved. Affected turf becomes weakened, chlorotic, thin,

and unsightly.

|

Click on images for

larger version

Figure 3. Leaf

rust infecting tall

fescue leaves; the leaf to the right

is healthy (courtesy L.T. Lucas).

|

Back to Top

The cycle of development for these rust fungi is very complex because of the

many species involved (about 30 in the United States, see Table

1, Figure 4 and Figure

5.) and the numerous alternate hosts, mostly woody shrubs and herbaceous

ornamentals. The alternate hosts are not believed to play an important role

in the disease development of the rust fungi that attack turfgrasses.

The yellow-orange to rust-colored powdery material that rubs off is composed

of tremendous numbers of microscopic spores (urediospores, uredospores, or urediniospores;

Figure 4 and Figure 5)

the reproductive structures of the rust fungi (Puccinia species). A single

pustule may contain 50,000 or more spores, each capable of producing a new infection.

These spores are readily disseminated by air currents, water, shoes, turf equipment,

infected sod, plugs, or sprigs. Some spores land on susceptible leaf tissue,

where, in the presence of moisture, they germinate by developing germ tubes

that penetrate the grass leaves and sheaths through open pores (stomates) and

cause infection. Most spores do not successfully reach a turf plant. A new generation

of rust pustules and urediospores appear 7 to 15 days later, depending largely

on the temperature. Urediospores constitute the repeating stage of the rust

fungus. This cycle of spore production, release, penetration, and infection

may be repeated a number of times during the summer and fall, or until environmental

conditions become unfavorable for the growth and reproduction of the rust fungus.

In mild climates, the rust fungi overwinter as dormant mycelium and as urediospores

in or on infected turfgrass foliage and equipment. In Illinois, rust fungi usually

overwinter as dormant mycelium within living grass leaves and crowns. When the

temperature (usually between 60° and 90° F or 15° to 32° C)

and moisture conditions are conducive to regrowth of the mycelium and germination

of the urediospores, the leaves and leaf sheaths become infected and a new generation

of redial pustules and their urediospores are formed. These spores are readily

transported over long distances by air currents, and those from southern regions

of the United States may serve as sources of windblown inoculum for northern

regions, where mycelium and urediospores cannot survive the winter.

Most rust fungi also produce another spore type, teliospores (Figure

4 and Figure 5), when the leaves senesce or dry

slowly. The brown to black telial stage is minor on mowed turfgrasses grown

under a good cultural management program. The teliospores, if produced, may

serve as overwintering structures in the north, germinating in the spring to

produce a third spore type, basidiospores. Basidiospores are transported by

air currents to the leaves of nearby, alternate hosts (mostly woody shrubs and

herbaceous ornamentals), where they may germinate and infect resulting in two

more spore types, pycniospores, and later, the aeciospores. Cluster cups or

aecial form on the alternate hosts and release aeciospores which are then capable

of infecting grass plants giving rise to urediospores, thus completing the disease

or life cycle. The urediospores are most important in infection of mowed turfgrasses.

Infection for most rusts is favored by 4 to 8 hours of low light intensity,

temperatures of 70° to 75° F (21° to 24° C), and high humidity,

heavy dews, or light rains followed by 8 to 16 hours of high light intensity,

temperatures of 80° to 95° F (27° to 35° C), and slow drying

of leaf surfaces. Stripe or yellow rust is active in northern states in early

spring and fall. Along the Pacific Coast it is active during the winter months.

Back to Top

-

Plant rust-resistant grasses, blends, or mixtures locally adapted for your

area. Check with your area Extension office or Extension turf specialist

for suggested grass species and cultivars to grow. Kentucky bluegrass cultivars

with moderate to good resistance to one or more rust include A-20 and A-34

(Bensun), Adelphi, Admiral, America, Apart, Aquila, Argyle, Aspen, Banff,

Bayside, Bonnieblue, Bono, Bristol, Brunswick, Challenger, Charlotte, Classic,

Columbia, Enmundi, Enoble, Escort, Fylking, Geronimo, Glade, Harmony, Holiday,

Majestic, Midnight, Mona, Monopoly, Mosa, Mystic, Nassau, Nugget, Parade,

Park, Piedmont, Plush, Ram I, Rugby, Sasta, Sydsport, Trenton, Vantage,

Victa, Wabash, and Welcome (see Table 2).

Other resistant grasses include Ensylva, Flyer, and Shadow fine-leaved fescues;

All-Star, Birdie II, Blazer, CBS II, Citation II, Cowboy, Dasher, Delray,

Elka, Fiesta, Gator, Loretta, Manhattan II, Omega II, Palmer, Pennant, Prelude,

Premier, Repell, Tara, and Yorktown perennial ryegrasses. Emerald and Meyer

zoysiagrasses are very susceptible; Belair has some resistance. Bermudagrass,

Italian or annual bluegrass, and tall fescue cultivars also differ in resistance.

Common and many hybrid bermudagrasses are tolerant or resistant while the

hybrid Sunturf is very susceptible.

Tall fescue cultivars with improved crown rust resistance include Adventure,

Apache, Falcon, Jaquar, Mustang, and Olympic. Resistance to rusts is limited

by the presence of numerous physiological races of the rust fungi. A cultivar

in one location may be resistant whereas it appears susceptible in another

turfgrass area.

-

Fertilize to keep grass growing at a steady rate, about an inch a week,

during summer or early fall droughts. The growth of grass blades pushes

the rust-infected leaves outward, where they can be mowed off and removed.

To increase vigor, maintain a proper balance of nitrogen, phosphorus, and

potassium (N-P-K), according to local recommendations and a soil test report.

These recommendations will vary with the grasses grown and their use. Do

not overfertilize, especially with a readily available high-nitrogen

source. Keep the phosphorus and potassium levels high.

-

During summer or early fall droughts, water established turf thoroughly

early in the day so that the grass can dry before night. Water infrequently

and deeply, moisten in the soil at each watering to a depth of 6 inches

or more. Avoid frequent light sprinklings, especially in the late afternoon

or evening. Free water on the leaf surface for several hours enhances development

of rusts and many other diseases.

-

Increase light penetration, air movement, and rapid drying of the grass

surface by pruning or selectively removing dense trees and shrubs bordering

the turf. Space landscape plants properly to allow adequate air movement

and to avoid excessive shade.

-

Remove thatch in early spring or early fall during cool weather when it

has accumulated to half an inch. Use a "vertical mower", "power rake", "aerifier",

or similar equipment. This equipment can be rented at most large garden

supply or tool rental stores.

-

Mow frequently at the weight recommended for your area and for the grasses

grown. Mow upright grasses, such as Kentucky bluegrass, ryegrasses, and

fescues, at 1˝ to 3˝ inches (somewhat higher in the summer). Creeping grasses

like bentgrasses, bermudagrass, and zoysias may be mowed to one-half inch

or less. Remove no more than a third of the leaf surface at one cutting.

Collect the clippings where feasible. This eliminates a potential source

of inoculum.

-

Follow suggested weed-control programs for the area and for the grasses

grown.

- The cultural practices outlined above (1 through 7) should provide for a

steady, vigorous growth of grass during extended, warm to hot, dry periods

when rust attacks are most severe. If rusts are serious year after year, these

practices may need to be supplemented by a preventive fungicide spray program.

The initial application should be made when rust is first evident on the grass

blades. Repeat applications are needed at 7- to 14-day intervals as long as

rust is prevalent. Sterol-inhibiting fungicides such as Bayleton, will provide

several weeks of protection with a single application. For best results, apply

the fungicide soon after mowing and removal of the clipping. Good coverage

of the leaf surface is necessary for control. The addition of about a half

teaspoonful of commercial "spreader-sticker" or surfactant (about ˝ to 1 teaspoonful

per gal or 1 pint to 1 quart per 100 gal) such as Plyac Non Ionic Spreader-Sticker,

De-pester Spreader-Activator, Ortho Spreader-Sticker, Triton B-1956, Bio-Film

Spreader-Sticker, Chevron Spray Sticker, Miller NuFilm-17 and NuFilm P, or

X-77. Always follow the manufacturer’s directions. For the most effective

control of rusts, uniformly spray 1000 sq ft of turf with 2 to 3 gal of water

containing one of the suggested fungicides listed in the current edition

of Illinois Commercial Landscape and Turfgrass Pest Management Handbook.

Use the lower fungicide rates in a routine preventive program; use

the higher rates for a curative program, after the appearance of numerous

infections (light yellow flecks).

Any one of these fungicides may be alternated with another fungicide, such

as Chipco 26019, Dyrene or Dymec, Vorlan, Cleary’s 3336, Fungo 50, Kromad,

or Tersan 1991.

If Pythium blight is also a problem, alternate one of the fungicides suggested

to control rusts, with a fungicide to control Pythium.

When mixing or applying any fungicide, follow the manufacturer’s directions

and precautions carefully.

(Mention of a trade name or proprietary product does not constitute warranty

of the product and does not imply approval of this material to the exclusion

of comparable products that may be equally suitable.)

Back to Top

[ Figure 1 ] [ Figure

2 ] [ Figure 3 ] [ Figure

4 ] [ Figure 5 ] [ Table

1 ] [ Table 2 ]

|