"We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." --Aristotle

Address any questions or comments regarding this newsletter to the individual authors listed after each article or to its editor, Rick Weinzierl, 217-333-6651, weinzier@illinois.edu. To receive e-mail notification of new postings of this newsletter, call or write the same number or address.

In This Issue:

Research Specialist Position at St. Charles Open for Applications

Regional Updates (from western Illinois)

Notes from Chris Doll (heat; assessing fruit maturity; drops; quick notes)

Fruit Production and Pest Management (when to harvest Honeycrisp apples; oriental fruit moth and codling moth updates)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management (hot weather and cucurbit fruit quality; corn earworm updates; more on pumpkin insects and insecticides; twospotted spider mites)

Local Foods Issues (reminder on survey of Internet and social media usage)

Upcoming Programs

- Good Agricultural Practices Webinar Series, August 6-27, 2012. University of Illinois Extension will be hosting a Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) webinar series on Mondays (August 6, 13, 20, and 27) from 6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. For more information, see http://web.extension.illinois.edu/gkw or contact University of Illinois Extension, Kankakee County, at 815-933-8337.

- Is Entrepreneurial Farming for You? August 6, 2012. This workshop will provide assistance to aspiring farmers with new business ideas at The Land Connection office in Bloomington from 5:30-8:30 p.m. For more information and to register, see: http://www.thelandconnection.org/training-farmers/entrepreneurial-farming-for-you/ or contact Jodi Stalsworth at info@thelandconnection.org or call 217-840-2128.

- Central Illinois Sustainable Farming Network Twilight Tour, August 7, 2012. Learn about Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) - harvest, storage, handling, pricing, and marketing at Samara Farm in Shelbyville from 5:30-8 p.m. For more information, see https://webs.extension.uiuc.edu/registration/?RegistrationID=6646 or contact Deborah Cavanaugh-Grant at cvnghgrn@illinois.edu, 217-782-4617.

- Illinois Organic Growers Association 2012 Field Days. The Illinois Organic Growers Association has scheduled six field days in August and September. See the details at http://illinoisorganicgrowers.org/2012/07/03/2012-ioga-field-day-schedule/ .

- Sustainable Agriculture Tour Peasants’ Plot Farm Peasants’ Plot Farm, August 10, 2012. 9:00 am - 10:30. Discussion topics will include crop rotation, manure, compost, and biopesticides. For more information and to register, call 815-933-8337 or email James Theuri at jtheu50@illinois.edu. Directions: From I-57, take exit 322 (Manteno) and go west on 9000 Rd (2.9 miles); turn right onto N 15000N Rd (1 mile); turn left onto W 10000N Rd (0.6 mile); the address is 2047 W 10000N Road.

- Income Opportunities for Small Acreages Workshop, September 4, 2012. 8:45 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. at the University of Illinois Extension Office, 980 North Postville Drive Lincoln, Illinois 62656. Topics will include: services and programs available for small farmers from NRCS & SWCD, farm records USDA programs, organic certification, what’s new in organic farming research, and becoming an organic farmer For more information, contact Amber Patrick at 309-833-4747.

- Living on the Land, October 1 through November 9, 2012. An 8-week series held on Mondays from 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. at the University of Illinois Extension Office, Will County, 100 Manhattan Road, Joliet, IL 60433. $150 per person for the series and $100 for an additional farm/family members. For more information, contact James Theuri at 815-933-8337 or jtheu50@illinois.edu.

Research Specialist Position at St. Charles Open for Applications

The University of Illinois is seeking applicants for a Research Specialist position at the St. Charles Horticulture Research Center. This is the position that Bill Shoemaker held for many years prior to his retirement at the end of June. The full position announcement and a link to the application process are available online at https://jobs.illinois.edu/default.cfm?page=job&jobID=20885. The deadline for applications is August 17, 2012.

This is a 12-month, permanent position (at least as permanent as positions can be in this day and age ... it is not grant-funded or term-limited). It is categorized as an academic professional position (not tenure-track, but also not civil-service). This is a great opportunity for someone interested in contributing to fruit and vegetable research and outreach and the expansion of local food systems. A Master’s degree is required ... other details are described in the online listing.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Regional Updates

... from western Illinois ...

I'm wondering how hard it could be to be a meteorologist in the Midwest. You wouldn't have to vary the report much since for the past 6 weeks there hasn't really been any deviation in the weather: highs in the 90's (or above) and no chance of rain. And unfortunately, the forecast for the Quincy area the past month has been all too accurate.

If you're not providing water to small fruits and vegetables, you don't have much to harvest. The triple-digit high temps of last week sure brought an end to many nonirrigated crops. One thing the dry weather has provided is a very low level of plant disease. At least one disease doesn't require much free moisture to infect ... powdery mildew can be a major disease for several crops, one of which is pumpkins. There are a number of PM "tolerant" pumpkin varieties, and most growers choose to include at least one of these. There are varieties with single parents and some with both parents carrying the PM gene, and control or prevention of PM varies according to variety and disease pressure. There really aren't any "resistant" varieties, but the level of tolerance can certainly impact how early or late in the season the disease develops.

This is the first tomato crop for many homeowners in the past several years. Extremely wet conditions brought on terrible growing conditions in 2009-11, making for poor growth and abundant disease pressure. This year it seems everyone who waters has tomatoes ... and blossom end rot is very common in many backyards.

Spider mites can be found in several crops including tomato. Cucumber beetles (spotted and striped) and western corn rootworm beetles can be easily found in many vine crops. Squash bugs have been laying eggs for several weeks. Japanese beetles are still present but in much lower numbers. Aphids can also be found in melons (and in other crops).

Blackberry harvest has slowed or stopped, and many report a decent yield considering the lack of rain. For those who had use of it, irrigation helped immensely, which can be said for all crops this year. The extreme heat has really advanced the growth of all crops this year; sweet corn growers report overlapping of split plantings, 6" pumpkins are not uncommon on plants, and Red Haven peach season was over this year when normally it's just beginning. Fall crop raspberries may not amount to much unless water has been used to stimulate growth.

Many insects help provide pollination for the pumpkin crop, including honey bees, native bees, cucumber beetles, corn rootworm beetles, etc. Because pumpkins produce both male and female blossoms, pollen has to be carried to female flowers for pollination to take place. Several visits are required and must be completed in just one morning, as blossoms are only open for one day, and depending upon moisture/stress levels, may not remain open for very long. Some pumpkin varieties are said to produce and abundance of male flowers over female flowers when hot conditions persist. As squash bugs and beetles become more numerous and insecticides are used for control, use caution to avoid bee mortality. Spray in late afternoon, after flowers close, using a liquid (not a dry powder or a WP) insecticide. Rick Weinzierl's note later in this issue provides some more details and precautions.

Mike Roegge (217-223-8380; roeggem@illinois.edu)

Notes from Chris Doll

Old notes are sometimes interesting to compare with what is current. On July 21, 2010, peaches were being harvested during some miserable 100 degree temperatures, but the month had yielded 6.5 inches of rain so that the fruit had good size and quality. My records show 0.35 inches of rain during the last 46 days, and July had maximum temperatures below 90 on two days, with 14 days 100 degrees or higher. Needless to say, it is rough on both growers and crops. The harvest season continues to be at least two weeks ahead of last year, and the end of the peach season except for the late varieties is about over, and the maturity time of apple varieties like Jonathan and Delicious is undecided. In apples, red color was nearly nil until the last weekend when the thermometer stayed below 90 degrees for two days. The sugars are building enough so that some pigment changed at that time. Early soluble solids tests on Jonathans reached 12-14 percent. It's doubtful if any ethephon will be used this year to advance maturity.

Dr. Kushad has an article on determining maturity and harvest timing for Honeycrisp apples later in this issue. For more information on testing apple maturity for harvest and storage, Win Cowgill and Jon Clements wrote an excellent summary in the July 31, 2012 issue of the Rutgers Fruit Plant and Pest Advisory ... lots of practical information and links to additional references.

A worrisome problem for apple growers is the amount of drops under Jonathans and a few other varieties. Some may be push-offs, but many are loose. It is early for NAA (and of questionable time and temperature for Retain), but after applying 10 ppm to a couple of early varieties late last week, they have stopped dropping. Dr. Kushad had an excellent article about stop-drop causes and controls in the July 19 issue of this newsletter, so reviewing it might help. My thoughts are that the local apple crop is good by volume, and that the fruit should stay on the tree for maturity and quality and yield. The market demand appears promising, but some time is needed for the 'normal' fall apple seasonal demand to kick in.

Sometimes some good comes with the bad. The summer's drought has minimized the pressure of most fruit diseases. A grower friend reported that for the first time in several years, the pestiferous bitter rot is missing. Grape growers are reporting the same thing, and the Back-40 grapes have had not pesticide sprays since May 8 (because of a 90 percent freeze kill) and now during veraison, they remain clean from both insects and disease. For a commercial crop, it would be stressful to gamble like that.

Quick Notes:

- A couple of weeks remain of the normal season for leaf or petiole collection of various fruit crops for leaf analysis. Recognize that the lack of rainfall might leave a heavy deposit of dust and competing chemicals on the leaf surface. Washing and drying might be required.

- Modification of the method of nitrating matted row strawberries in mid-August might have to be changed unless the rains begin. Of course, if nitrogen rates were sufficient during renovation, we have not lost much from leaching.

- Thornless blackberry vines in this area have finished fruiting and are making lots of cane growth, with the terminals growing into the rat-tail stage. Under present dry conditions, those rat-tail tips will have a difficult time developing roots.

- August or between final peach harvest and first fall apple harvest is a good time to prepare young orchards for cover crop seeding in September. Every year is different, and this will be no exception.

Chris Doll

Fruit Production and Pest Management

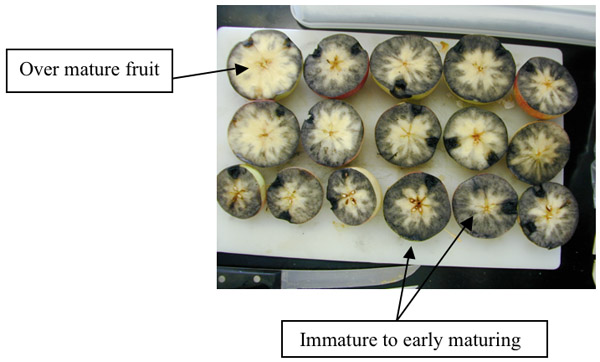

Know when to Harvest Honeycrisp Apples. The hot and dry weather is affecting fruit maturity and color development. Honeycrisp at the U of I Farm look like Golden Delicious. Maturity of most apple varieties can be predicted by color, firmness, soluble solids, and starch breakdown. Firmness of 15 to 20 lb, soluble solids of 12% or higher, and at least 50% of the starch has been converted into sugars are considered ideal maturity standards for most apple cultivars. However, like Gala, Honeycrisp fruits tend to ripen unevenly on the tree. There is a lot of variability in maturity from fruit to fruit. As you can see from the starch breakdown in the photograph below, some fruits maybe over mature while others are immature.

Soluble solids also vary quite a bit from fruit to fruit. So what difference does it make to have different maturity levels between fruit? Well, very little if you plan to sell the fruits soon after harvest. However, if you plan to store the fruit for more than two months then problems will show up after storage. Two of the most serious problems are bitter pit and soft scald. Bitter pit is a physiological disorder that most believe is associated with calcium deficiency. It shows mostly on fruits that are harvest immature. While soft scald, also a physiological disorder, develops in fruits that are harvested over mature.

Bitter pit symptoms (left) and soft scald (brown skin) (right).

To overcome bitter pit, spray fruit with calcium before harvest and do not harvest immature fruits. As for soft scald, do not harvest ove- mature fruits. Soft scald injury can also be reduced by storing fruits at 36 to 38oF, rather than 30oF, which is the temperature recommended for most other apple varieties. Harvesting over mature fruits and storing them at the colder temperature can also lead to internal breakdown. Because of the variability in maturity among Honeycrisp fruits, it is recommended that you spot pick fruits you plan to store for more than two months. Use ground color or the greener side of the fruit to estimate maturity. Pick fruits when the ground color is pale green, but not cream. You can also reduce the internal breakdown and soft scald by conditioning the fruits for a few hours at 50 to 60 oF before you put them in cold storage, especially for fruits harvest on hot days.

Watercore symptoms are high in many varieties including Honeycrisp. Watercore is a physiological disorder that results from disruption of the sugar (sorbitol) conversion to starch inside the fruit. The flesh of fruits that have watercore is glossy around the vascular bundle. In severe cases, the symptoms can be visible from the outside of the fruit ( I have several fruits this year) . Hot and dry weather usually results in higher percentage of sorbitol symptoms on some varieties like Red Delicious, Honeycrisp, Fuji, Gala, and Jonathan. Fruits with watercore taste sweet but they deteriorate very rapidly in storage. So, if you see any symptoms of watercore on the fruit, harvest the fruits quickly, keep them in a cool place for at least twenty four hours before putting them in cold storage and don't store them for more than a few weeks.

Gala fruits showing watercore symptoms.

Mosbah Kushad (217-244-5691; kushad@illinois.edu)

Notes on Oriental Fruit Moth and Codling Moth

By this time of year, generations of oriental fruit moth and even codling moth begin to overlap, with gaps or peaks in flight intensity and egg-laying sometimes dependent on how well earlier sprays worked at preventing infestations and reproduction within individual orchards. The best approach to determining the need and timing for sprays to control these insects for the remainder of the season is to monitor pheromone traps in individual orchards. Remember that most insecticides used in apples (and a few late peaches) now are intended to kill larvae as they hatch from eggs, so spray timing should follow the capture of moths in traps by a few days ... codling moth egg hatch begins about 240 DD base 50 F after eggs are deposited. The previous two issues of this newsletters have listed the required preharvest intervals for effective insecticides ... be sure to time sprays and harvests so that the required "waiting period" has elapsed before treated fruits are picked.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management

Impact of the Hot and Dry Weather on Cucurbit Fruit Quality

This year's record dry and hot weather has many growers asking about its effect on fruit maturity, quality, and storage potential of pumpkins and other cucurbits. I have visited several growers in central and northern Illinois, and my overall observation is that most plants looked healthy with little visible signs of stress. However, if this hot and dry weather continues, it is likely that nonirrigated plants will shut down their growth, causing leaves to brown and fruits to develop blotchy color before they reach adequate maturity. If this happens, then fruits will not be of good quality and will not keep well in storage. On the other hand if the plants stay green until the fruits reach normal maturity, then the fruits will be of adequate quality and will keep in storage, probably better than in wet years.

What should be done if the weather stays dry and you don't have irrigation? Pay attention to fruit maturity. Immature fruits will have relatively soft or soggy rind, uneven and dull color, and a skin surface that looks stressed. The best quality fruits that will store well are those that have reached full maturity. In general, cucurbit crops vary widely in their harvest time and storage requirements, depending on cultivar and location. For example, Jack-o-lantern harvest in Illinois usually starts in mid-September to October, while cantaloupe harvest starts as early as mid-July and continues as late as the end of September. Cucurbit crops also vary in their storage requirements. Some, such as summer squash and zucchini, are extremely sensitive to low temperature storage, while others, such as pickling cucumbers, are more forgiving.

Uneven maturity in pumpkin fruit.

When to harvest? Fruits harvested at the correct stage of maturity will keep longer in storage and maintain better quality. Harvest pumpkins when they reach maturity or full color. For those that have pick-your-own operations, cut the vine off of mature fruits to cure fruit, stiffen the handle, reduce disease infection, and slow down shrinkage. Pumpkins will continue to develop color after harvest, but pay attention to maturity. Fully green fruits will develop some color, but those fruits will not store as well as fruits that are harvested mature.

Cucumbers are harvested immature in order to keep that crisp and juicy texture and to keep the seed coat from hardening. Squash and summer squash grow very quickly when the temperature is between 77 and 95°F. Picking is recommended every day, every other day, or every 3 to 4 days after pollination in order to maintain the fresh and tender flesh and glossy skin look.

Cantaloupes (or more appropriately muskmelons) are generally considered climacteric fruits. In other words, they produce ethylene and may continue to ripen after they reach a physiological stage of maturity. However, some non-netted melons are possibly non climacteric, and so they will not ripen much after harvest. Several factors are used to determine when to harvest muskmelons. Some older cultivars emit a fragrant aroma ("musk") when fully ripe. Other factors that have been used to measure muskmelon maturity include development of fully netted skin, yellow or orange ground color, percent soluble solids, development of the abscission zone, and days from antheses. However, the most widely used factors in determining maturity for harvest of muskmelon fruits is the full slip state of the fruit from the vine. Muskmelon fruits will soften if kept at room temperature, but their sugar level will not increase. Most consumers perceive a soft muskmelon to be sweeter than a hard one even when their sugar levels are similar.

In contrast to pumpkin, and muskmelon, watermelon will not continue to ripen after harvest. Therefore, knowing when to harvest watermelon is important. Most pickers use darkening of the small tendril next to the fruit as an indicator of maturity. Crews of most large farms often pick fruits when the ground color (the side of the fruit in contact with the soil) of the rind turns yellow. Days from planting, usually 75 to 95 days, is used as an approximate indicator of harvest maturity. Among consumers, watermelon maturity attracts more attention than any other fruit. Thumbing, shaking, squeezing, and rolling are but a few of the ways consumers use to pick a ripe watermelon. My father's sure way to pick a ripe watermelon was to hold one end of the fruit between the palms of both hands, usually the end away from the stem, and squeeze while sticking his ear to listen for a crackling sound. If he heard a crackling sound then he was "certain and definite" that the fruit is ripe. I am not sure if there is watermelon in the afterlife ... if there is, he is out there squeezing the daylight out of them.

Handling and transportation. Bruising by mishandling the fruit at harvest and during transportation is one of the most serious problems for all cucurbits varieties. Throwing or dropping fruits into a bin or stacking too many fruits on top of each often result in unnecessary bruises that affect quality and the cosmetic look of the fruit. Bruised fruits do not store as long and develop bitter taste in storage. Bruised fruits are also more susceptible to chilling injury. To avoid bruising, train your pickers to handle the fruits properly, avoid stacking fruits too high on top of each other, and avoid storing or stacking tender fruits on top of hard surfaces such as concrete. Another important factor that affects quality is keeping the fruit in the sun for a long period. Fruits that have been kept in the sun for more than one hour soften quickly and do not keep long in storage.

Curing after harvest. Curing of certain cucurbits, such as pumpkins and hard-rind squashes, is a standard practice to harden the peel in order to increase shelf-life and reduce disease infection. Curing of pumpkin also helps the handle stay firm. Do not cure certain types of squash, including acorn and other delicate cultivars, so they don't lose their quality due to the high temperature. Curing is usually done by holding the fruit at 80 to 85°F and about 90% relative humidity for 7 to 10 days in storage, depending on the weather conditions before harvest. Pumpkins can also be cured in the field by placing them in windrows. Dry and warm (but not hot) weather before harvest reduces the need for longer curing time.

Handling. Fruit should be harvested early in the morning and placed in the shade soon after harvest. It is best to store pumpkin and other fruits in a cooler. However, any cool space is better than keeping the fruits outside exposed to direct sunlight. There is a misconception among growers that pumpkins should not be stored on a concrete floor. This is true only if the fruit temperature and the floor temperature are widely different. Moisture (sweating) often builds on the underside of the fruit when the floor temperature is significantly lower than the fruit temperature (or visa-versa). To prevent this from happening, keep the fruits on a wagon or in boxes for a day before placing them on the floor until the temperature of the fruit and the floor evens up. Another important practice is to avoid stacking pumpkin fruits more than four high. Bruising is not always visible. As was mentioned earlier, bruised fruits do not store as long as healthy fruits and the taste of edible bruised fruits is not as good as non-bruised fruits. Bruising can be prevented by training pickers to handle the fruit properly and to use soft surfaces to place the fruits on. Bruising is more severe in summer squash, slicing cucumber, netted and non-netted muskmelons. More importantly, firm fruits are damaged more by bruising than soft or ripe fruits. The damaged area in bruised fruits rots much faster than the rest of the fruit, which leads to rot development.

Storage. Selecting the appropriate storage temperature not only maintains quality but also keeps the fruit in good shape for the longest time possible. Most cucurbit crops can be stored together under similar conditions although a more refined storage temperature and humidity will lengthen the storage period. Also, the shelf-life of different cucurbits will vary depending on the cultivars. The flowing table lists ideal temperatures for storing different cucurbits.

Ideal storage temperatures and percent humidity for several cucurbit crops.

Cucurbit crop |

Ideal Storage Conditions |

Approximate |

|

Temperature |

Relative Humidity |

Shelf-Life |

|

|

°F |

(%) |

|

Cucumber pickling |

40 |

95+ |

7 to 8 days |

Slicing cucumber |

50-55 |

85-90 |

10-14 days |

Summer squash |

50-55 |

95+ |

7-14 days |

Winter Squash |

45-50 |

50-70 |

60-90 days |

Pumpkin |

55-60 |

50-70 |

60-90 days |

Watermelon |

50-60 |

90-95 |

14-21 days |

Netted muskmelon/cantaloupe |

40-45 |

95+ |

8 to 12 days |

Non netted melons -- Casaba, Crenshaw, honeydew, etc., |

45-50 |

85-90 |

15-20 days |

Mosbah Kushad (217-244-5691; kushad@illinois.edu)

Corn Earworm Flights

Corn earworm pheromone traps in most parts of the state have been capturing moths in low numbers (<5 to around 20 per night) but fairly consistently for the last two weeks. Counts have been considerably higher at the Dixon Springs Agricultural Center in far southern Illinois (ranging from 20 to greater than 100 per night) and at Urbana (ranging from 25 to 175 per night). Most Illinois sweet corn growers whose markets demand very little or no corn earworm damage should be spraying at about 3-day intervals from first silk to brown silk to prevent infestations unless traps near their fields have not been capturing moths. See previous issues of this newsletter for discussions of effective insecticides and application intervals. Results of trapping at a few locations are posted on the North Central IPM PIPE (Pest Information Platform for Extension and Education) website - http://apps.csi.iastate.edu/pipe/?c=entry&a=view&id=68.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

More on Pumpkin Insects and Insecticides

Mike Roegge pointed out that several pests may be present in pumpkins now and that controlling them when the crop is in bloom and bees are present presents real challenges. Some brief recommendations and reminders:

Squash bug control is warranted if scouting reveals more than one egg mass per plant, and the best timing for insecticide applications to control them is when the nymphs have just hatched. The most effective insecticides for squash bug control are the pyrethroids, particularly Brigade, Warrior, Mustang Max, Baythroid, and generic products that contain the same active ingredients. All of these are Restricted-Use insecticides; applicators must have a Pesticide Applicator's License to purchase and use them. All are also highly toxic to bees, so if they must be used, they should be applied only late in the day when blossoms are closed, and honey bee hives should be closed to prevent foraging on the treated crop for 24 hours after application. Sevin XLR Plus (NOT other formulations of Sevin) is not nearly as effective for squash bug control, but is perhaps the best option for conventional growers who do not have an Applicator's License. It too should be used only late in the day after blossoms have closed and bees are not foraging. Organic growers have no truly effective options for controlling this insect once it is present in pumpkins and squash.

Squash vine borer infestations in most areas are already established, and larvae have tunneled into the bases of vines. These infestations cannot be controlled by applications of insecticides. Where moth flight and egg-laying is still ongoing, the pyrethroids listed above are the most effective treatments to prevent new infestations. See the July 5 issue of this newsletter for more about this insect. Again, there are no truly effective treatments for organic growers to use to kill this pest once it has reached squash or pumpkin plantings.

Aphids on pumpkins are often most numerous where the crop has been sprayed repeatedly with pyrethroids or Sevin to control cucumber beetles, squash bugs, and squash vine borer. These sprays are not really effective against aphids but kill their natural enemies, including lady beetles and lacewings ... this is one of several reasons NOT to use these insecticides routinely if infestations of these insects don't really warrant control. Where aphids warrant control and the crop is in bloom, Assail and Fulfill are more effective and less toxic to bees than most other labeled insecticides. Nonetheless, application late in the day after blooms have closed is still recommended. Organic growers can achieve some aphid control with products that control neem or insecticidal soaps such as M-Pede, but thorough coverage of the lower surface of leaves is essential (and difficult). Actara, Admire, and Platinum are labeled for use as foliar sprays or application through trickle irrigation for aphid control in pumpkins, but recent research by Dively and Kamel indicates that these insecticides DO move into nectar and pollen and that concentrations are highest when applications are made during or only shortly before bloom. Although the concentrations of these compounds in pollen and nectar gathered by bees may not be lethal to them, these findings suggest that using these neonicotinoids at this time of year may be unnecessarily risky.

Cucumber beetles and western corn rootworm beetles will be feeding on foliage and fruit for the next few weeks. The pyrethroids listed above for squash bug control and Sevin XLR Plus are effective against these insects, but the comments about spray timing to reduce bee kill are relevant for these applications as well.

Toxicity of various pesticides to bees is summarized in several publications. Two that are readily available on the web are published by Purdue University and Clemson University.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Twospotted Spider Mites

Twospotted spider mite (left, from Forestry Images) and injury (right, from Forestry Images).

Twospotted spider mites are causing stippling, yellowing, and bronzing of foliage on a range of crops including soybeans, tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, cucumbers, melons, and green beans. Infestations typically start along field edges or waterways, especially if ditchbank vegetation is allowed to grow tall and is then mowed, triggering the mites' movement to adjacent green crops. They secrete silken webbing that helps them to become windborne and disperse well into fields in a short time.

Control: As with aphids (and even more so), most of the insecticides used to control common insect pests on vegetable crops do not control mites and may even trigger their outbreaks because applications kill the mites' natural enemies. Miticide registrations differ among crops, so as is the case for many insecticides, some can be used on one vegetable crop but not another. Page 30 of the 2012 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide provides a partial listing label status, and preharvest intervals of insecticides/miticides for most vegetable crops. Some effective miticides that can be used on vegetables include Acramite (3-day PHI on cucumbers, melons, squash, pumpkins, eggplant, peppers, tomatoes, and beans), Agi-Mek (7-day PHI on cucumbers, melons, squash, pumpkins, eggplant, peppers, and tomatoes), and Oberon (7-day PHI on cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, and squash; 1-day PHI on eggplant, peppers, and tomatoes). Kelthane remains labeled for some vegetable crops ... se the 2012 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide for complete listings.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Local Foods Issues

Survey Opportunity: Farmers' Use of the Internet and Farm Business Practices and Perspectives

A reminder from the previous issue of this newsletter ...

Researchers at the University of Illinois have developed an online survey to better understand the needs of Illinois fruit and vegetable growers for information and training on the use of social media in marketing their produce. The results of this survey will help improve their understanding of how farmers use online tools and networking and how these activities affect your farm. Results will also us in designing future educational programs.

To fill out the survey, please click on the link below or copy and paste it into your Web browser: http://go.illinois.edu/farmersurvey

As a small token of gratitude, you will be given the opportunity to enter your name at the end of the survey for the chance to win one of two $50 prepaid Visa gift cards, which can be used anywhere Visa is accepted as a form of payment. Odds of winning will be about 1 in 250. Only one entry per household is permitted, and you can only take the survey once during the time period the survey is open. The survey will be open for about two weeks.

I know your time is incredibly valuable, especially at this time of year, so this survey is designed to take no more than 20 to 30 minutes to complete. No identifying information will be shared or connected with your responses in the survey. If you have any questions about this study or problems taking the survey, please contact me at kabrams@illinois.edu, 217-244-3682.

Katie Abrams, Agricultural Communications, University of Illinois (217-244-3682; kabrams@illinois.edu)

Less Seriously ...

Things you don't want to hear during surgery:

- Better save that. We'll need it for the autopsy.

- Bo! Bo! Come back with that. Bad dog!

- Wait a minute, if this is his spleen, then what's that?

- Ya know, there's big money in kidneys, and this guy's got two of 'em.

- That's cool. Now can you make his leg twitch by pressing that one.

- OK, now take a picture from this angle. This is truly a freak of nature.

- Nurse, did this patient sign an organ donation card?

University of Illinois Extension Specialists in Fruit and Vegetable Production & Pest Management

Extension Educators – Local Food Systems and Small Farms |

||

Bronwyn Aly, Gallatin, Hamilton, Hardin, Pope, Saline, and White counties |

618-382-2662 |

|

Katie Bell, Franklin, Jackson, Perry, Randolph, & Williamson counties |

618-687-1727 |

|

Sarah Farley, Lake & McHenry counties |

847-223-8627 |

|

Nick Frillman, Woodford, Livingston, & McLean counties |

309-663-8306 |

|

Laurie George, Bond, Clinton, Jefferson, Marion, & Washington counties |

618-548-1446 |

|

Zachary Grant, Cook County | 708-679-6889 | |

Doug Gucker, DeWitt, Macon, and Piatt counties |

217-877-6042 |

|

Erin Harper, Champaign, Ford, Iroquois, and Vermillion counties |

217-333-7672 |

|

Grace Margherio, Jackie Joyner-Kersee Center, St. Clair County |

217-244-3547 |

|

Grant McCarty, Jo Daviess, Stephenson, and Winnebago counties |

815-235-4125 |

|

Katie Parker, Adams, Brown, Hancock, Pike and Schuyler counties |

217-223-8380 |

|

Kathryn Pereira, Cook County |

773-233-2900 |

|

James Theuri, Grundy, Kankakee, and Will counties |

815-933-8337 |

|

Extension Educators – Horticulture |

||

Chris Enroth, Henderson, Knox, McDonough, and Warren counties |

309-837-3939 |

|

Richard Hentschel, DuPage, Kane, and Kendall counties |

630-584-6166 |

|

Andrew Holsinger, Christian, Jersey, Macoupin, & Montgomery counties |

217-532-3941 |

|

Extension Educators - Commercial Agriculture |

||

Elizabeth Wahle, Fruit & Vegetable Production |

618-344-4230 |

|

Nathan Johanning, Madison, Monroe & St. Clair counties |

618-939-3434 |

|

Campus-based Extension Specialists |

||

Kacie Athey, Entomology |

217-244-9916 |

|

Mohammad Babadoost, Plant Pathology |

217-333-1523 |

|