"We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." --Aristotle

Address any questions or comments regarding this newsletter to the individual authors listed after each article or to its editor, Rick Weinzierl, 217-333-6651, weinzier@illinois.edu. To receive e-mail notification of new postings of this newsletter, call or write the same number or address.

In This Issue:

Upcoming Programs (for beginning and established growers)

Regional Reports (from southern and western Illinois)

Fruit Production and Pest Management (updates on codling moth and oriental fruit moth; upcoming timing for San Jose scale crawler control; monitoring and controlling spotted wing Drosophila; black knot of plum)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management (cover crop notes)

Upcoming Programs

Check the Illinois SARE calendar for a full list of programs and links for registration.

http://illinoissare.org/ and http://illinoissare.org/calendar.php

Also see the University of Illinois Extension Local Food Systems and Small Farms Team's web site at:

http://web.extension.illinois.edu/smallfarm/ and their calendar of events at http://web.extension.illinois.edu/units/calendar.cfm?UnitID=629.

- GAPs (Good Agricultural Practices) webinars, postponed to July, 2014. Call 815-933-8337 or email uie-gkw@illinois.edu for more information on webinar dates and registration, or contact a Local Food Systems and Small Farms educator in your area (see the staff list and contact info at the end of this newsletter).

- Illinois Summer Horticulture Field Day, June 12, 2014. Schwartz Orchard, Centralia, IL. See www.schwartzfruitfarm.com and/or www.specialtygrowers.org for more information. For reservations, email www.ilsthortsoc@yahoo.com or phone 309/828/8929.

Regional Reports

From southern Illinois ... Wet and cool pretty well sums it up! In Murphysboro we have had around 4 inches of rain since last Friday (May 9), with anywhere from heavy downpours to just light rain throughout the day. In addition to the rain, temperatures have dropped and we are entering into "blackberry winter" with highs the next few days around 60 and lows in the 40s. And of course blackberries are blooming as well. Winter injury has varied according to variety and exposure of the field. As an example of this, at home I have 'Dirksen' which is leafing out and starting to bloom with very little die back on the florocanes. However, I also have 'Black Satin' nearby and most of the florocanes have been killed back except for a few scattered buds here and there. Other reports from area growers have 'Natchez' in mid to late bloom and 'Chester' in early bloom, with both showing very minimal winter injury.

High tunnel tomatoes are slow to grow during cool cloudy days, but with decent weather by the end of May we will see the first tomato harvest. Many have early sweet corn plantings up and growing, although some plantings that coincided with previous cool/damp weather saw stand reductions due to the weather; others that germinated during warmer periods had no problem. Tree fruit are progressing well, although growers are certainly worried about disease management given the wet weather we have had the last few days. I think everyone is looking at the forecast and looking forward to the prospect of warm, sunny conditions next week!

Nathan Johanning (618-939-3434; njohann@illinois.edu)

From western Illinois ... We finally received some much needed moisture the evening of May 12. Amounts varied, but most report rainfall totals from 1.75" to over 2.5". This was the first significant moisture we've received since early April. Unfortunately, most of it came in an hour's time. But soils were very dry and quite a bit did soak in.

High tunnel tomatoes have been growing very fast with the warm temperatures of the past week, inches of new growth per day. Staking, tying, and suckering have been ongoing. The past two weeks has seen both high tunnel tomatoes and peppers initiate flowering.

Producers have been busy planting/transplanting, laying plastic, irrigating and doing other types of field work. With the warm temperatures and dry soil conditions until recently, irrigation of newly set transplants had been an important concern.

All but one of eight matted row strawberry varieties is flowering in our variety trials (Jewel is the only one not in bloom). It doesn't appear that excessive winter cold temperatures affected bloom at all. Plasticulture berries have advanced to the stage where small green berries are evident. High tunnel strawberry harvest has begun, and most producers are happy with yields.

Mites and aphids often overwinter on crops held over in a high tunnel. With warmer temperatures and a lack of predators in high tunnels, these populations can explode. Both these insects have been detected in strawberry plants overwintering in some tunnels. Take time now to examine overwintering as well as newly transplanted crops into tunnels that had an overwintering crop.

Asparagus harvest quickly became overwhelming as the temperatures reached 85 plus degrees. Now that we're seeing temperatures cool, harvest has been cut to less than half of those large harvest amounts. Asparagus harvest should cease when a majority of the spears are pencil size or smaller in diameter. The spears that emerge from the plant all spring are the result of crown and root resources that accumulated after harvest last year through fern die back late last fall. As the plant exhausts these reserves, spears become weaker and their diameter becomes thinner, which signals the time to "put the bed to sleep" for the year. At this time, fertilize with 50-70 lbs / acre of nitrogen and take soil tests to determine phosphorus and potassium needs, then apply as necessary. Asparagus requires high levels of both P and K. Weed control is accomplished by using one of several labeled herbicides. The addition of Gramoxone with the residual will help control emerged annual weeds, without harming the emerged asparagus (although any emerged spears will be lost). The herbicide application should be timed to occur immediately after the last harvest. For a listing of labeled products on asparagus (and many other products), see the 2014 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide. Asparagus beetle is usually an annual pest that can inflict injury to growing asparagus. This season (so far) that particular pest has been absent.

Surviving peach fruits are ½" as are early apples. Blueberries are at full bloom, depending upon variety. Evidence of winter injury on brambles is readily apparent. New primocane growth from crowns is upwards of 12" in height. Winter injury on florocanes is evident, and new growth is occurring on surviving tissue.

Mike Roegge (217-223-8380; roeggem@illinois.edu)

Fruit Production and Pest Management

Oriental Fruit Moth and Codling Moth

Later this week I should have information for additional locations, but for now, I have biofix dates only for Urbana ... first sustained captures of oriental fruit moth began on April 26, and first sustained captures of codling moth began on May 9. Using the degree-day calculator on the Illinois State Water Survey's WARM website, degree-day accumulations for these insects at Urbana are ...

|

Degree-days, base 50 F, since biofix |

Degree-days, base 45 F, since biofix |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Through May 14 |

Projected for May 21 |

Projected for May 28 |

Through May 14 |

Projected for May 21 |

Projected for May 28 |

|

Oriental Fruit Moth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urbana - biofix |

|

|

|

283 |

404 |

530 |

Codling Moth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urbana - biofix |

90 |

180 |

273 |

|

|

|

For oriental fruit moth, where mating disruption is used, application of dispensers may be done before first flight begins or can be delayed to target seconds and later generations. The later application must be done before second generation flight begins at approximately 950 degree-days (base 45F) after biofix ... still a few weeks in the future during this year's cold spring.

For codling moth, egg hatch begins at approximately 220 degree-days after biofix, and application timing for different insecticides varies from 100 to 250 degree-days after biofix. See page 23 of the 2014 Midwest Tree Fruit Spray Guide for listings of recommended timing for different insecticides. (Use https://store.extension.iastate.edu/Product/2014-Midwest-Tree-Fruit-Spray-Guide and click on the download link to obtain a free pdf of this publication).

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Insecticides for San Jose Scale Crawler Control

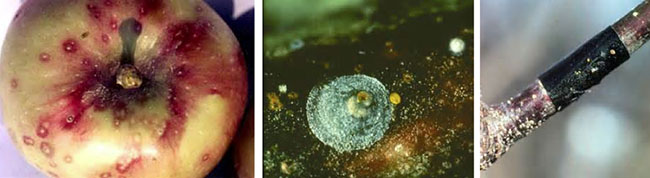

San Jose scale remains a problem in many peach and apple orchards in the Midwest. If infestations have persisted after prebloom applications of oil, crawlers (immature scales that have just moved out from under their mother's hardened scale) appear a few weeks after bloom. To monitor for crawlers (and thereby know when to spray), wrap black electrical tape around twigs on trees in areas where twig or fruit infestations were observed last year. The crawlers that will be caught on the tape are yellowish very small ... see the illustrations below. Insecticides labeled for crawler control include Esteem, Assail, Centaur, and Movento (as well as Diazinon). Esteem and Centaur are rated as excellent for San Jose scale crawler control.

From left: San Jose scale-infested fruit; close-up of San Jose scale and crawlers on a twig; black electrical tape used to trap crawlers on a twig.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Spotted Wing Drosophila

Everyone growing blueberries, blackberries, and raspberries should be monitoring in 2014 for spotted wing Drosophila, an invasive pest that infests thin-skinned fruits as they ripen. This insect is known to be present in much of Illinois and will damage these crops severely, making the fruits unmarketable. Peaches, tomatoes, and grapes also are suitable host plants.

As I have noted previously in this newsletter, there is lots of useful information on this insect on a Michigan State University web site devoted to it ... http://www.ipm.msu.edu/invasive_species/spotted_wing_drosophila. A section on monitoring includes instructions on how to make and use traps to detect this insect's presence.

Some simple instructions for making traps ...

- If you don't want to sort through the bait liquid described below, order some sticky yellow cards from

Great Lakes IPM (800-235-0285). Do this first so that they arrive in the mail by the time you've completed steps 2 and 3. See page 25 of the online catalog ... a package of 25 3" x 5" cards sells for $8.75. You will cut them in half, so 25 of them will allow you to run 5 traps for 10 weeks. Order a larger number if you need more. - Get and make the traps ... use 1-quart deli cups, preferably clear. (Go to a supermarket with a deli, and if they will not sell you empty containers, buy some potato salad or whatever, and save the container and lid.) Make at least 2 holes near the top of the container so that you can run wire or string through them to hang the containers. Make at 8-10 more holes along the side of the container at least 2-3 inches above the bottom ... these will let flies in. The holes should be about the diameter of a number 2 pencil. Use a drill, a paper punch, or a heated metal rod to melt through the plastic. Hang half of a yellow sticky card (3" x 2½") from the lid.

- Prepare the liquid bait that draws fruit flies to the trap. You can use apple cider vinegar or a mixture of ¼ oz. yeast, 4 teaspoons of sugar, and 12 oz. of water. Pour the bait into the trap to a depth of about 1 inch.

- Hang traps in the shade about waist high in area where ripening fruit is present. Check the traps and replace the bait liquid weekly and discard the old bait liquid away from the trap. Use at least 2 traps for each separate patch or location for each crop. Male spotted wing Drosophila fruit flies have a dark spot on each wing. If you think you have detected this insect, send specimens to me or contact me by email ... Rick Weinzierl, 1102 S. Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, IL 61820; 217-244-2126, weinzier@illinois.edu.

In general, insecticides that have short PHIs (preharvest intervals) and have been shown to be effective against spotted wing Drosophila include ...

Insecticide |

PHI (days) in Blueberries |

PHI (days) in Brambles |

Days of Residual Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

Malathion |

1 |

1 |

5-7 |

Imidan |

3 |

Not labeled |

7 |

Mustang Max |

1 |

1 |

7 |

Danitol |

3 |

3 |

7 |

Brigade |

1 |

3 |

7 |

Delegate |

3 |

1 |

7 |

Entrust (OMRI) |

3 |

1 |

3-5 |

Pyganic (OMRI) |

(12 hours, REI) |

(12 hours, REI ) |

2 |

Estimates of residual activity are adapted from work done by Rufus Isaacs and reported on the Michigan State University web site listed above.

Left: Confirmed distribution of spotted wing Drosophila in Illinois, October, 2013. Center and right: Spotted wing Drosophila trap and adult male.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

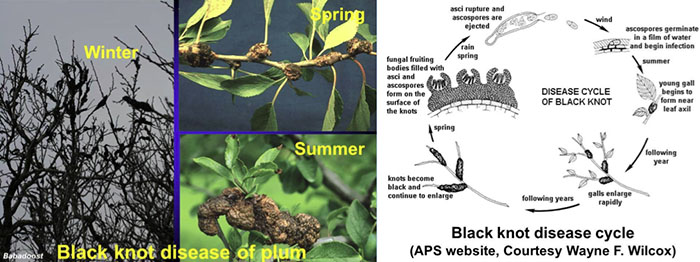

Black Knot of Plum

Black knot of plum, caused by the fungus Apiosporina morbosa, is a common disease in Illinois. Black knot was first described in 1821 in Pennsylvania. The fungus also affects prune and cherry, but infection of these crops in Illinois is not common. The disease affects only woody parts of trees, primarily twigs, and is characterized by elongated swellings 0.5 -1.2 inches long and 1-3 inches in circumference. Development of black knots may not be noticed until the winter of the second season of infection. The first symptoms appear as small, light brown swellings of the current or previous season's growth. Over the growing season the knots become dark and hard. The hard, black knots are the typical symptoms associated with the disease.

The fungus overwinters in the knots. About the time of bud emergence in the spring, the first spores (ascospores) are released following a period of warm, wet weather. Temperatures between 60 and 80°F are ideal for infection of new plant tissue. The ascospores are spread by air currents and rain splashing. The succulent green shoots are most susceptible to infection by ascospores. Ascospore discharge continues for 2-3 weeks after bloom. The knots develop slowly, and by the end of the summer they appear only as small galls that could easily be overlooked. Further development of knots does not occur until the following spring when the knots enlarge very rapidly. Gradually asexual spores (conidia) develop on the surface of knots. The conidia are disseminated by wind and splashing rain and may cause secondary infection.

Management of black knot is achieved by cultural practices, genetic resistance, and chemical control. The main practice to lower disease incidence is the removal of sources of inoculum. All shoots and branches bearing knots should be pruned out during the winter. Pruning should be made 6-8 inches below the knot to remove mycelium of the pathogen in asymptomatic tissues. Also, removal of sources of inoculum in nearby wild Prunus species in hedgerows and woodlots is necessary. The knots are capable of producing ascospores for some time after removal from the tree. Therefore, they should be burned, buried, or removed from the site regardless of the time of year the pruning takes place. Planting new trees near areas with known problems should be avoided. Plum varieties vary in their tolerance or resistance to black knot. It has been reported that Early Italian, Brodshaw, Fallenburg, Methley and Milton are somewhat less susceptible than Stanley; Shiro, Santa Rose, and Formosa are much less susceptible; and President is apparently resistant to black knot. Japanese varieties of plums are generally less susceptible than most American varieties.

Fungicides can be used for managing black knot. But fungicides should be used as protectants and with cultural practices. In application of fungicides, attention should be paid to inoculum levels and the weather conditions. Sites with severe black knot infections may require protective applications from early spring around bud break through summer. Where inoculum has been maintained at low to moderate levels, sprays are most likely to be useful from bud break through shuck split (the period of maximum availability of ascospores). Regardless of frequency, fungicides have been found to be most effective when applied prior to a rain and temperatures are above 60°F. Effective fungicides for control of black knot in Illinois are chlorothalonil (Bravo), Captan, Captivate, and C-M. For the most current fungicide recommendations for control of black knot, refer to the 2014 Midwest Tree Fruit Spray Guide. (Use https://store.extension.iastate.edu/Product/2014-Midwest-Tree-Fruit-Spray-Guide and click on the download link to obtain a free pdf of this publication).

Mohammad Babadoost (217-333-1523; babadoos@illinois.edu)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management

Cover Crop Notes: Terminating Cereal Grains

Cereal rye (winter rye), winter wheat, triticale, and other small grains are very popular cover crops, especially for no-till vegetable production. Now that we've finally gotten in to more spring-like weather, many of these cover crops have really taken off and many growers are thinking about terminating them.

If you are mowing or using a roller/crimper, anthesis (pollination) is the best time to terminate. Anthesis or flowering is easily distinguished as the time when you see yellow anthers hanging from the head (see picture above). This timing is recommended for these termination methods because at flowering the plant has switched from vegetative (stem/leaf) growth to reproductive growth and because of this, regrowth from the base of the plant is very limited. Prior to flowering the plant is still trying to produce vegetation so you can get a significant amount of regrowth. This is especially important to note if you are not wanting or able (organic systems) to use herbicides to manage regrowth.

Triticale at anthesis (flowering).

If you are strictly using herbicides (ie. glyphosate) for termination, you have more flexibility and can terminate earlier, but make sure to spray shortly after pollination (milk stage) again to prevent the formation of viable seeds.

Nathan Johanning (618-939-3434; njohann@illinois.edu)

University of Illinois Extension Specialists in Fruit and Vegetable Production & Pest Management

Extension Educators – Local Food Systems and Small Farms |

||

Bronwyn Aly, Gallatin, Hamilton, Hardin, Pope, Saline, and White counties |

618-382-2662 |

|

Katie Bell, Franklin, Jackson, Perry, Randolph, & Williamson counties |

618-687-1727 |

|

Sarah Farley, Lake & McHenry counties |

847-223-8627 |

|

Nick Frillman, Woodford, Livingston, & McLean counties |

309-663-8306 |

|

Laurie George, Bond, Clinton, Jefferson, Marion, & Washington counties |

618-548-1446 |

|

Zachary Grant, Cook County | 708-679-6889 | |

Doug Gucker, DeWitt, Macon, and Piatt counties |

217-877-6042 |

|

Erin Harper, Champaign, Ford, Iroquois, and Vermillion counties |

217-333-7672 |

|

Grace Margherio, Jackie Joyner-Kersee Center, St. Clair County |

217-244-3547 |

|

Grant McCarty, Jo Daviess, Stephenson, and Winnebago counties |

815-235-4125 |

|

Katie Parker, Adams, Brown, Hancock, Pike and Schuyler counties |

217-223-8380 |

|

Kathryn Pereira, Cook County |

773-233-2900 |

|

James Theuri, Grundy, Kankakee, and Will counties |

815-933-8337 |

|

Extension Educators – Horticulture |

||

Chris Enroth, Henderson, Knox, McDonough, and Warren counties |

309-837-3939 |

|

Richard Hentschel, DuPage, Kane, and Kendall counties |

630-584-6166 |

|

Andrew Holsinger, Christian, Jersey, Macoupin, & Montgomery counties |

217-532-3941 |

|

Extension Educators - Commercial Agriculture |

||

Elizabeth Wahle, Fruit & Vegetable Production |

618-344-4230 |

|

Nathan Johanning, Madison, Monroe & St. Clair counties |

618-939-3434 |

|

Campus-based Extension Specialists |

||

Kacie Athey, Entomology |

217-244-9916 |

|

Mohammad Babadoost, Plant Pathology |

217-333-1523 |

|