"We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." --Aristotle

Address any questions or comments regarding this newsletter to the individual authors listed after each article or to its editor, Rick Weinzierl, 217-333-6651, weinzier@illinois.edu. To receive e-mail notification of new postings of this newsletter, call or write the same number or address.

In This Issue:

Upcoming Programs (listings for beginning and established growers)

Regional Reports (from southern and western Illinois and Cook County)

Fruit Production and Pest Management (managing fungicide-resistant apple scab; spotted wing Drosophila)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management (soil testing; death by GMO tomato … satire, NOT truth)

Upcoming Programs

Check the Illinois SARE calendar for a full list of programs and links for registration.

http://illinoissare.org/ and http://illinoissare.org/calendar.php

Also see the University of Illinois Extension Local Food Systems and Small Farms Team's web site at:

http://web.extension.illinois.edu/smallfarm/ and their calendar of events at http://web.extension.illinois.edu/units/calendar.cfm?UnitID=629.

- Spring Cover Crop Field Day, March 26, 2015. 9:00 a.m. – noon, Ewing Demonstration Center, 16132 N. Ewing Rd; Ewing, IL. See cover crop plots and learn more about how cover crops can help your crop production system. Program is free and lunch is included. For more details visit http://web.extension.illinois.edu/units/event.cfm?UnitID=629&EventID=68306 or contact Nathan Johanning at njohann@illinois.edu or 618-687-1727.

- Workshops on the Affordable Care Act (morning) and Succession Planning (afternoon), March 26, 2015. Illinois Farm Bureau Building, Bloomington, IL. No fee, but registration is required; see www.specialtygrowers.org to register. For more information, contact Diane Handley at dhandly@ilfb.org or 309-557-2107.

- Midwest School for Beginning Grape Growers, March 29-31, 2015. Madison, Wisconsin. An intensive 3-day course covering market assessment and profitability, site selection and soil preparation, variety selection, pest management, economics, equipment, and labor. Registration fee = $375. For registration information, contact Peter Werts at pwerts@ipminstitute.org or 608-265-3704; for content questions, contact John Hendrickson at jhendric@wisc.edu or 608-265-3704.

- Purdue Viticulture Field Day, April 8, 2015. Dulcius Vineyards, Columbia City, IN. Focus will be on re-establishing vines after the harsh winter. $30 advanced registration required; registration limited to 50. Contact Lori Jolly-Brown at 765- 494-1296 or ljollybr@purdue.edu.

- Opportunities in Local and Regional Foods Conference, March 31, 2015. 7:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., Lewis and Clark Community College. For more information, email altonabda2012@gmail.com or call 618-551-5020. Register at www.MarketFreshNetwork.org.

- Farmers Market and Local Food Production Promotion Program Grant Writing Workshops, April 8, 15, and 23, 2015. (1:00 – 5:00 p.m., April 8 in Springfield at the Sangamon County Extension Office; April 15 in Mt. Vernon at the Jefferson County Extension Office; April 23 in Grayslake at the Lake County Extension Office. For more information, contact Deborah Cavanaugh-Grant at cvnghgrn@illinois.edu or 217-782-4617. Register at https://web.extension.illinois.edu/registration/?RegistrationID=11736.

- Southwestern Illinois Twilight Orchard Meetings, April 16 and May 21, 2015. April 16 at Eckert's Orchard near Grafton; May 21 at Weigel Orchard near Golden Eagle. 5:30 – 7:30 p.m. at each location. For more information, contact Ken Johnson at 217-243-7424 or kjohnso@illinois.edu.

- Southern Illinois Summer Twilight Series, May through August, 2015. May 18 at Miller Farms, Campbell Hill; June 15 at Ridge Road Vineyard, Pulaski, IL; July 20 at Sunnybrook Gardens, Carmi, IL; and August 10 at Darn Hot Peppers, Cobden, IL. 6:00 – 8:00 p.m. for each program. Register online at http://web.extension.illinois.edu/ghhpsw/ or contact Bronwyn Aly at 618-382-2662 or baly@illinois.edu or Nathan Johanning at 618-687-1727 or njohann@illinois.edu.

- Midwest Compost School, June 2-4, 2015. Wauconda Township Hall, Lake County, IL. For more information, contact Duane Friend at friend@illinois.edu or 217-243-7424. Register at http://extension.illinois.edu/go/midwestcompost.

Regional Reports

From southern Illinois ... Temperatures have finally moderated somewhat to more spring-like conditions; however the last few days we have cooled again with highs on March 18 in 40s. There were even a few brief light sleet showers in Union County on the 18th. Heavy rains on March 13 brought around 2-3 inches of rain to the area, leaving things very wet. Sun, wind, and moderate temperatures have helped to dry soils a little, but very we still have a ways to go before we can get underway with much spring field preparation.

Many peach growers have been checking buds on trees for winter injury from the cold snap we had back around February 19. I have heard reports of temperatures south of Murphysboro, from -5 down to -15. From state weather stations at Carbondale and Dixon Springs, low temperatures for the 19th were -12.1 and -9.6, respectively. So far I have heard of a partial loss of some flower buds on certain varieties and locations, but nothing widespread.

Plasticulture strawberry row covers are being removed with the warmer days, and plants look to be developing well with good crown formation. Many growers are anxiously waiting for the current cold spell to pass so they can transplant tomatoes and other warm season vegetables into high tunnels. In our demonstration high tunnel, cool season greens are doing well. We have been battling an "explosion" of aphids, first on spinach and then later on lettuce and carrots. While I have not observed any visual injury yet, I am trying to reduce the populations, because I do not want them to get a start on other newly transplanted warm season vegetables. For more information on specific management practice for aphids refer to the 2015 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide.

Nathan Johanning (618-939-3434; njohann@illinois.edu)

From western Illinois ... We've missed the rains for the past two weeks and on Monday, when the high was 80 and the winds were brisk, the well-drained worked soils were beginning to dry out on top. It wouldn't surprise me if there were a few who got out on Tuesday to plant their potatoes. In our part of the world, St. Patrick's Day is the traditional potato planting day, although in some years there is still snow on the ground.

For those of you still contemplating strawberry variety selection, I'd point out the variety trial we've conducted the past two years comparing some of the newer varieties to older standby varieties. You can find this info at: http://web.extension.illinois.edu/abhps/cat88_4076.html.

The past week has really pushed development of perennial fruit crops. We're beginning to see some early green on the blackberries here. Apple and peach buds are swelling, as are buds on blueberries. Pruning of brambles should be ongoing, and apple growers are still working that task. I usually wait to prune my 3 peach trees until the threat of frost has ended, but then it doesn't take me long to prune! Peaches here are absolutely loaded with buds, so it will be essential to thin heavily if Mother Nature allows the full crop to set.

Straw should be pulled from matted row strawberries when soil temperatures under the straw are 40-42 degrees F. The temperature recorded on March 18 here was right at 40 degrees. Brad Bergefurd, OSU, recommends that plasticulture strawberry growers remove covers when temperatures average 50 degrees daily. I was tempted this weekend to remove our covers and probably should have.

It's getting close to the time to begin management of asparagus for central Illinois growers. We've always mowed off the dead ferns April 1 and applied a pre-emergence herbicide (and maybe add some glyphosate if dandelions or other early season perennials are emerged). Some folks prefer to burn off the residue. We've never disked the soil … for two reasons. First, the fine feeder roots of asparagus are located throughout the top 12" of soil. They can be injured by even shallow disking (and that could perhaps allow fusarium crown rot to develop). The second reason is soil erosion. Having a little cover and a fairly firm soil can help reduce erosion.

Mike Roegge (217-223-8380; roeggem@illinois.edu)

From Cook County and the Chicago metropolitan area … The production season has begun, at least for those using high tunnels or starting their own transplants. If you run a highly diversified farm, your greenhouse or seed starting room is likely full with Allium family crops and early Brassica transplants. Even if you do not grow a significant number of transplants, spring bed prep and those first direct seeding planting windows should be firmly planted in your mind.

Most of the area surrounding Chicago is technically within hardiness zone 5b. However, the large thermal mass created by Lake Michigan and the urban heating effect create an interesting microclimate east of I-294 and closer to the lake. This small oval microclimate is technically in hardiness zone 6a, which makes it closer to a growing climate found in southern Illinois! Here is a handy link to figuring out last frost dates for your specific area (very useful in timing plantings): http://www.isws.illinois.edu/atmos/statecli/Frost/frost.htm. Another useful link lists soil temperatures: http://www.isws.illinois.edu/warm/soil/. Here you can find the nearest weather monitoring station to your farm and track soil temperature. Nothing replaces going out into the field and measuring this yourself, but it is a handy tool in the meantime. When soil temperatures creep past 45 F, cold hardy crops such as spinach will readily begin germinating.

The below link will lead you to a general sheet for information about planting dates specifically for Cook County. If you are in the zone 6a oval, planting towards the beginning of the date ranges provided would be advised. Again, these are general dates, and should be adjusted to your specific microclimate. Keep tuned to this link for updates on these planting dates: http://web.extension.illinois.edu/cook/cat88_3498.html.

You can also consult planting date charts for high tunnels for early season production at

https://hoophouse.msu.edu/assets/custom/files/Cool%20Season%20Crops-Winter%20Planting%20Chart%202013.pdf and https://hoophouse.msu.edu/assets/custom/files/Warm%20Season%20Crops%20Schedule.pdf. These tables are from Michigan State University and are a mainly applicable to hardiness zone 5b at latitude 42 N. Be cautious when using these dates, and experiment with earlier or later dates within the date ranges depending on which direction north or south you are from 42 N Latitude. The further north you are from 42 N, plant a little later, and the opposite may apply the further south you move from 42 N.

Zachary Grant (708-449-4320; zgrant2@illinois.edu)

Fruit Production and Pest Management

Managing Fungicide-Resistant Apple Scab

Apple scab, caused by the fungus Venturia inaequalis, is one of the most important apple and crabapple diseases in Illinois. Apple scab develops in all unsprayed orchards in Illinois. The losses from apple scab are: (1) yield reduction; (2) fruit quality reduction; (3) premature defoliation; (4) weakened trees; and (5) increased production costs.

The first scab infections appear on the under surface of the flower sepals or flower cluster leaves as small, irregular spots that range from light brown to olive green. Gradually, all leaves may be infected. As the infection progresses, the spots become circular and slightly velvety and olive green. The spots gradually turn dark brown to metallic black. Tissue around the scab thickens, causing the upper surface of the lesion to be convex and the leaves become dwarfed, curled, and scorched at the margins. Petioles (leaf stems) are also infected by the scab fungus, which results in early defoliation. Early defoliation results in reduced fruit bud development for the next year's crop.

Fruit infections appear a few weeks after bloom as nearly circular, velvety, dark olive green lesions with the cuticle ruptured at the margins. Older lesions become black, scabby, and fruit often cracks. This cracking of the fruit provides avenues of infection for various rot-producing fungi. Severe early infection results in deformed fruit. Later infections result in small lesions either in the orchard or during storage.

The scab fungus overwinters in infected leaves that have fallen to the ground. The fungus forms fruiting bodies (pseudothecia) which are embedded in the leaves near the surface. Sacs (asci) filled with the primary or spring spores of the fungus (ascospores) start to develop within the pseudothecia during winter and spring and mature at the time of bud break (green tip). Mature ascospores are released in early spring; usually peaks are during the time from pink through bloom. Ascospores are blown to nearby trees by wind currents, then germinate in a film of water on the surface of leaves and fruit and infect the tissues. On each infection site, thousands of secondary or summer spores (conidia) are produced, which are dispersed and cause new (secondary) infections. Because numerous additional conidia are produced on each new spot, repeated secondary infections have an epidemic effect on disease development.

Severe Apple Leaf and Fruit Scab

During 2011-2013, severe scab was observed in some apple orchards in Illinois. Incidence of scabby fruit of some varieties (e.g., Fuji) exceeded 50% in one orchard. Samples of infected fruit were tested for resistance of the fungus to fungicides. The results showed that there were strains of V. inaequalis resistant to the fungicides Rally (myclobutanil), Sovran (kresoxim-methyl), and Syllit (dodine), which are major scab fungicides in Illinois. Modes of action of these fungicides are 3, 11, and M for Rally, Sovran, and Syllit, respectively, as identified by the fungicide resistance action committee (FRAC).

To develop effective management of resistant strains of the scab fungus, the following treatments were considered in the apple orchard with the most severe scab infection in 2012 and 2013. To reduce the overwintering scab fungus, leaf litter was reduced by moving leaves on the orchard floor after leaf drop in the fall and application of 5% urea (approximately 40 pounds urea in 100 gallons of water) onto leaves on the orchard floor. To prevent spread of inoculum from crab apple trees to apple trees, crab apple trees at the edges of the orchard were removed. To increase air movement in the canopy and improve coverage of canopy with fungicides, apple trees were pruned properly. To prevent infection of apple tissues, application of fungicides began at green-tip and continued through the fist-cover spray at 7-day intervals in blocks that had heavy leaf and fruit scab during 2011-2013. Fungicides used were Captan 80WDG at 5 pound per acre (lb/A), Dithane M-45 at 3-4 lb/A, Inspire Super at 12 fl oz/A, and Fontelis at 20 fl oz/A. Captan + Dithane M-45 + Inspire Super were applied at green-tip, tight cluster, and one week after petal fall (the first-cover). Dithane M-45 + Fontelis were applied at ½-inch green, apple pink, and petal fall. During summer, all blocks in the orchard were sprayed with the same fungicides of the grower's choice. Not even a single scabby apple was found in the blocks that received the above-mentioned treatments, while scabby apples were observed in the blocks with different fungicide applications. For effective management of apple scab in Illinois in 2015, the following practices are recommended; moving leaves and application of urea in the fall (after leaf fall) or in winter/spring (before tree growth), proper pruning of trees, effective management of crab apple scab at the edges of the orchard (if there are any), and application of Mancozeb (e.g., Dithane M-45) + Inspire Super alternated with Mancozeb + Fontelis from the green-tip to petal fall, at 7-day intervals. Recommendations on the labels of fungicides should be closely followed. For additional information on management of apple diseases, refer to the 2015 Midwest Tree Fruit Spray Guide.

Mohammad Babadoost (217-333-1523; babadoos@illinois.edu)

Spotted Wing Drosophila

Yes, it's still just March. But yes, NOW is the time to plan and prepare for managing spotted wing Drosophila (SWD) this summer in thin-skinned fruit crops. SWD was first detected in the US in 2008. It spread rapidly throughout the country and was first recorded in Illinois in 2012. It has been "officially" recorded in counties on the northern and southern tips of the state and in counties on our eastern and western state lines … I am nearly certain that it is present in all Illinois counties.

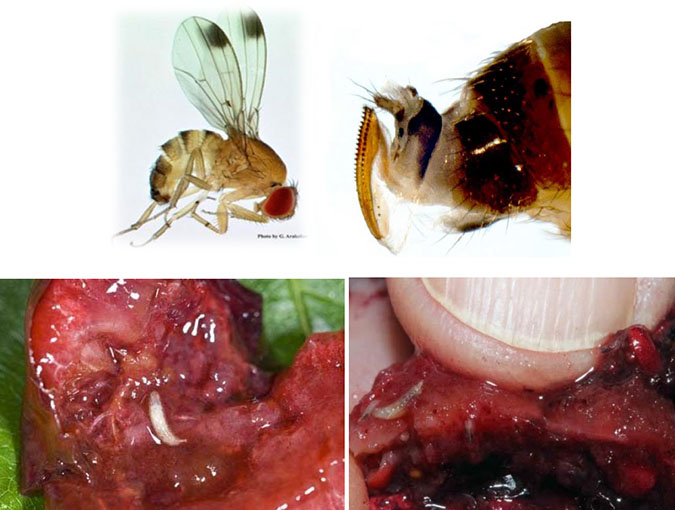

Adult male SWD flies have a prominent spot on each wing (hence the name), but the wings of females are not spotted. Females of this species differ from other Drosophila species by having an ovipositor (egg-laying organ) that is serrated or saw-like. This characteristic enables them to cut open the "skin" of thin-skinned fruits and lay eggs into them as they begin to ripen. Larvae (maggots) develop with fruits and can be present at harvest; we have collected as many as 50 larvae from a single raspberry that appeared to be just prefect for harvest and sale. It infests a wide range of common fruit crops including blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, peaches, strawberries, cherries, and grapes. We also have reared it from mulberries, elderberries, black currents, Japanese honeysuckle, and pokeweed berries. Infested fruits appear nearly normal at first when larvae are newly hatched and just beginning to feed, but within 36 to 48 hours the fruit begins to "melt down" and collapse, and larvae become clearly visible.

Top: Adult male SWD (left) and ovipositor of female (right). Bottom: SWD larvae in raspberries.

If you grow blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, cherries, peaches, or grapes (or less common fruits such as mulberries, currants, or elderberries), you MUST manage this insect unless you plan to eat or sell infested fruit. Where harvest of matted-row or plasticulture strawberries ends before mid- to late June, the crop will likely escape infestation. Similarly, early blueberry varieties may ripen before infestations become common. These escapes occur because numbers of SWD that survive the winter are relatively low, and they appear to become active in mid-June to early July. Populations build up rapidly through the summer (with a little lull in the very hottest weather), and the likelihood of heavy infestations increases through fall. SWD flies DO enter high tunnels and lay eggs into blackberries, raspberries, and day-neutral strawberries grown in these structures.

A key step in managing SWD is monitoring … for adult flies and larvae in fruit:

To monitor adult SWD flies, use 1-quart cups with lures and soapy water. You can make traps or buy them ready-to-use from Great Lakes IPM. Some simple instructions for making traps ...

- If you don't want to sort through the soapy liquid in the bottom of the trap, order some sticky yellow cards from Great Lakes IPM (800-235-0285). Do this first so that they arrive in the mail by the time you've completed steps 2 and 3. See page 25 of the Great Lakes IPM online catalog ... a package of 25 3" x 5" cards sells for $8.75. You will cut them in half, so 25 of them will allow you to run 5 traps for 10 weeks. Order a larger number if you need more.

- To make traps, use 1-quart deli cups, preferably clear. (Go to a supermarket with a deli, and if they will not sell you empty containers, buy some potato salad or whatever, and save the container and lid.) Make at least 2 holes near the top of the container so that you can run wire or string through them to hang the containers. Make 8-10 more holes along the side of the container at least 2-3 inches above the bottom ... these will let flies in. The holes should be about the diameter of a number 2 pencil. Use a drill, a paper punch, or a heated metal rod to melt through the plastic. Use a paper clip or a wire to hang half of a yellow sticky card (3" x 2½") from the lid. SWD lures can be purchased from Great Lakes IPM (800-235-0285). Hang these lures inside the deli cups, and add about 1 inch of soapy water as a drowning agent (make by adding 1 teaspoon of borax plus one drop of unscented dish detergent to a quart of water). You can buy traps already-made if you prefer … see NEW SPOTTED WING DROSOPHILA TRAP AND DUAL LURE at the bottom of page 17 of the Great Lakes IPM catalog or call them at 800-235-0285.

- Hang traps in the shade about waist-high in areas where ripening fruit is present. Check the traps and replace the liquid weekly. Replace the lures every 4 weeks. If you need help identifying specimens, call me or contact me by email for instructions on sending them in – Rick Weinzierl, 217-244-2126, weinzier@illinois.edu.

- Traps provide indications of SWD population levels but do NOT necessarily provide advance warning of the need for your first spray … in my observations here and in Rufus Isaac's work in Michigan, infested fruit samples have been collected before SWD adults have been trapped in small fruit plantings. Placing a few traps in adjacent woods may increase the chance of earlier detection, but initiation of sprays or other practices should begin at fruit coloring even if traps have not yet caught SWD adults.

Left: home-made SWD trap; center: close-up of lures and card; right: commercially available SWD trap.

To determine whether or not fruit is infested, immerse a sample of harvested fruit in a fairly high concentration sugar-water solution – 1 cup granulated white sugar per 1 quart water. Within one-half hour (and in fact sooner) larvae will float to the surface. I put berries into small-mesh produce bags and place a washer (weight) on top so that the fruit remains submerged as the larvae float to the surface. The reasons to assess infestations in fruit are two-fold … one is to determine how effective your control programs have been, and the second more critical reason is to detect infestation before you sell infested fruit to valued customers who did not want to see maggots squirming in it a day later.

So, a summary on monitoring …

- If SWD was present in 2014, start management with first signs of fruit coloring in susceptible crops in 2015 … do not wait to catch SWD adults in traps.

- Use traps baited with Trecé 2-part lures. Use yellow sticky cards and soapy water to capture flies. Lures, traps, and cards are available from Great Lakes IPM (800-235-0285)..

- Place some traps in adjacent woods for early detection.

- Assess fruit infestation by immersing fruit in sugar water (1 cup granulated white sugar in 1 quart water) … larvae will float to the surface.

To prevent infestations or at least limit losses to SWD, a combination of cultural and chemical approaches will be necessary for most growers. Clean picking and frequent picking (and removing damaged fruit) can reduce population buildups within plantings or high tunnels … not a total solution, but valuable nonetheless. Exclusion by use of screening or fine-mesh netting has been shown to reduce infestations as well. In the photo below from Rufus Isaacs at Michigan State University, workers are installing netting (ProtekNet netting FIIN 4X100-80, Dubois Agrinovation) on a high tunnel. In real-world settings, netting is difficult to use and generally will not completely exclude SWD flies, but in conjunction with insecticide applications to the crop, it can be beneficial (as long as it does not lead to too-high temperatures in the high tunnel or within a frame around a small number of plants).

Installing netting on ends of high tunnels for SWD suppression.

(Photo from Rufus Isaacs, Michigan State University)

Post-harvest chilling is also important for SWD control … or at least for suppressing its growth in harvested fruits. Refrigeration will prevent larval growth and slow fruit breakdown.

Insecticides are needed for effective control of SWD. They should be applied to blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, and similar small fruit crops beginning at the onset of fruit coloring and ripening. Preharvest intervals (PHIs) and recommended application intervals for several insecticides are listed in the table below. Two cautions: (1) Rotate among insecticide modes of action to avoid maximum selection for insecticide resistance (particularly, do not use just Brigade, Danitol, and Mustang Max … all are pyrethroids). (2) All of these insecticides are at least moderately toxic to bees, and in brambles and strawberries control may be necessary on ripening fruit while later blossoms are still attractive to bees. Where sprays must be applied, use liquid formulations and spray at night when bees are not foraging.

Selected insecticides for SWD control in blueberries, brambles, strawberries, and peaches. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Insecticide |

PHI (days) in Blueberries |

PHI (days) in Brambles |

PHI (days) in Strawberries |

PHI (days) in Peaches |

Recommended Application Interval1,2 |

Brigade |

1 |

3 |

0 |

Not labelled |

5-7 |

Danitol (fenpropathrin) |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

5-7 |

Delegate, Radiant |

3 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

5-7 |

Entrust (OMRI) |

3 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

3-5 |

Imidan |

3 |

Not labeled |

Not labeled |

14 |

7 |

Malathion |

1 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

3-5 |

Mustang Max |

1 |

1 |

Not labeled |

14 |

5-7 |

Pyganic (OMRI) |

(12 hours, REI) |

(12 hours, REI) |

(12 hours, REI) |

(12 hours, REI) |

1-2 |

1Interval based in part on estimates of residual activity from work done by Rufus Isaacs and in part from observations of effectiveness of spray programs in IL in 2013 and 2014. | |||||

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management

Soil Testing

I've been looking at soil test reports and providing soil fertility recommendations for over 30 years. And it amazes me still when I see soil test results that are way at either end of the spectrum – either off the charts high or so low you can't imagine how anything grows there. Not all tests fall into one of these categories, but it's amazing how many do!

And that tells me that there hasn't been a soil testing history. Soil tests should be conducted every 3-4 years because that's the way we chart how well we're managing the nutrition of our growing plants. We generally recommend taking soil samples 6-7" deep and using 4-5 subsamples to make one sample. One sample should represent 3-5 acres. Record where samples were taken if you want to vary the fertility due to extreme differences in results.

We generally like to compare samples taken during the same time frame, so sampling usually takes place in the fall or spring. Samples taken within 4-6 weeks of frost leaving the soil will result in somewhat higher potassium tests due to the fact that the soil clay that "trapped" potassium when it was frozen will slowly release it back, so adjust accordingly.

Most will recommend the following as baseline soil tests: pH range from 6.2-6.5; Phosphorus soil test of 30#/acre and potassium soil test of 300 lbs/ acre. For those soils with a CEC below 12, where it will be difficult for the soil to hold potassium, so try to achieve a soil test of 260 lbs/acre. Remember some labs will report in lbs/acre while others will report part per million (ppm). To convert, multiply ppm times 2 to arrive at lb/acre.

Once the soil is fertilized to optimal levels, divide fields, plots, or gardens into crop categories depending upon fertility needs and fertilize yearly for those categories. Nitrogen-loving crops (sweet corn, solanaceous crops, vine crops, etc.) will require higher amounts of that nutrient. Tomatoes like a higher potassium level as well. Legume crops (peas, beans, alfalfa, vetch and clovers) will provide nitrogen, so no need for that nutrient.

For a list of certified soil testing labs in Illinois, see the Illinois Soil Testing Association's website at http://www.soiltesting.org/.

Mike Roegge (217-223-8380; roeggem@illinois.edu)

Death by GMO Tomato ... Satire, NOT Truth

Earlier this week David Rosenberger, recently retired from Cornell University and the New York Agricultural Experiment Station, sent the applecrop list-serve a note warning of a recent internet story that originated in Europe. He wrote, "In case you missed it, you may want to read the following article which was forwarded thousands of times last week by folks concerned about GMOs" …

http://worldnewsdailyreport.com/doctors-confirm-first-human-death-officially-caused-by-gmos/

The story purports to reveal the death of a man in Spain, caused by his consumption of a genetically modified tomato containing genes from fish. It's a compelling story, but as it turns out, completely fictional. David's note continued, "The report didn't sound credible to me, and it was not as you will learn by reading the follow-up by a fact-checking website" … http://www.inquisitr.com/1899679/did-gmo-tomatoes-kill-juan-pedro-ramos/

This fact-check site notes, "The original article, which had been shared over 22.9 thousand times as of Thursday and featuring the alleged first person to die from eating a GMO, was published on the satirical news site World News Daily Report, which features a disclaimer that states, 'WNDR assumes however all responsibility for the satirical nature of its articles and for the fictional nature of their content. All characters appearing in the articles in this website – even those based on real people – are entirely fictional and any resemblance between them and any persons, living, dead, or undead is purely a miracle.'"

The fact-check story notes that there are no GMO tomatoes approved for sale in Europe and that the only GMO tomato ever to be marketed anywhere, the GMO Flavr-Saver tomato, did not contain any genes from fish. I'll add, it also is NOT marketed in the US either … its approval several years ago was followed by market failure, and it is not grown or marketed here.

This story is an example of the real problem that lots of what you read on the internet is not at all based on fact or even honest differences in interpretation of facts. There may be very legitimate reasons to question the sustainability of GMO corn, cotton, and soybean crops as currently used, but there is no credible research that indicates human health risks for currently available or likely to be approved GMO crops.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Less Seriously ...

(from a posting on the applecrop list-serve by Evan Milburn) ...

- 42.7 percent of all statistics are made up on the spot.

- A day without sunshine is like, night.

- I feel like I'm diagonally parked in a parallel universe.

- He who laughs last, thinks slowest.

- I drive way too fast to worry about cholesterol.

- Support bacteria. They're the only culture some people have.

- Plan to be spontaneous tomorrow.

- When everything is coming your way, you're in the wrong lane.

- OK, so what's the speed of dark?

University of Illinois Extension Specialists in Fruit and Vegetable Production & Pest Management

Extension Educators – Local Food Systems and Small Farms |

||

Bronwyn Aly, Gallatin, Hamilton, Hardin, Pope, Saline, and White counties |

618-382-2662 |

|

Katie Bell, Franklin, Jackson, Perry, Randolph, & Williamson counties |

618-687-1727 |

|

Sarah Farley, Lake & McHenry counties |

847-223-8627 |

|

Nick Frillman, Woodford, Livingston, & McLean counties |

309-663-8306 |

|

Laurie George, Bond, Clinton, Jefferson, Marion, & Washington counties |

618-548-1446 |

|

Zachary Grant, Cook County | 708-679-6889 | |

Doug Gucker, DeWitt, Macon, and Piatt counties |

217-877-6042 |

|

Erin Harper, Champaign, Ford, Iroquois, and Vermillion counties |

217-333-7672 |

|

Grace Margherio, Jackie Joyner-Kersee Center, St. Clair County |

217-244-3547 |

|

Grant McCarty, Jo Daviess, Stephenson, and Winnebago counties |

815-235-4125 |

|

Katie Parker, Adams, Brown, Hancock, Pike and Schuyler counties |

217-223-8380 |

|

Kathryn Pereira, Cook County |

773-233-2900 |

|

James Theuri, Grundy, Kankakee, and Will counties |

815-933-8337 |

|

Extension Educators – Horticulture |

||

Chris Enroth, Henderson, Knox, McDonough, and Warren counties |

309-837-3939 |

|

Richard Hentschel, DuPage, Kane, and Kendall counties |

630-584-6166 |

|

Andrew Holsinger, Christian, Jersey, Macoupin, & Montgomery counties |

217-532-3941 |

|

Extension Educators - Commercial Agriculture |

||

Elizabeth Wahle, Fruit & Vegetable Production |

618-344-4230 |

|

Nathan Johanning, Madison, Monroe & St. Clair counties |

618-939-3434 |

|

Campus-based Extension Specialists |

||

Kacie Athey, Entomology |

217-244-9916 |

|

Mohammad Babadoost, Plant Pathology |

217-333-1523 |

|