"We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." --Aristotle

Address any questions or comments regarding this newsletter to the individual authors listed after each article or to its editor, Rick Weinzierl, 217-333-6651, weinzier@illinois.edu. To receive e-mail notification of new postings of this newsletter, call or write the same number or address.

In This Issue:

Upcoming Programs (listings for beginning and established growers)

Regional Reports (from southern and western Illinois; departure of Kyle Cecil from Extension)

Fruit Production and Pest Management (periodical cicadas in the south, corn earworm in strawberries, potato leafhopper on apples, notes on brown marmorated stink bug, codling moth, and oriental fruit moth)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management (potato leafhopper on green beans and potatoes, corn earworm / tomato fruitworm, cucumber beetles)

Upcoming Programs

Check the Illinois SARE calendar for a full list of programs and links for registration.

http://illinoissare.org/ and http://illinoissare.org/calendar.php

Also see the University of Illinois Extension Local Food Systems and Small Farms Team's web site at:

http://web.extension.illinois.edu/smallfarm/ and their calendar of events at http://web.extension.illinois.edu/units/calendar.cfm?UnitID=629.

- Midwest Compost School, June 2-4, 2015. Wauconda Township Hall, Lake County, IL. For more information, contact Duane Friend at friend@illinois.edu or 217-243-7424. Register at http://extension.illinois.edu/go/midwestcompost.

- Quad Cities Pollinator Conference, June 10-11, 2015. Jumer's Casino and Hotel, Rock Island, IL. Registration deadline is June1 ... see http://nahantmarsh.org/qcpollinatorconference/.

- Illinois Summer Horticulture Day, June 11, 2015. 8:45 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. at Boggio's Orchard and Produce, 12087 IL Highway 71, Granville, IL 61326. Registration begins at 8:00 a.m. Advance registration is $25 and includes lunch. More information about Boggio's Orchard and Produce is available at www.boggiosorchardandproduce.com. Event information is available at http://www.specialtygrowers.org/illinois-state-horticultural-association.html. For questions and reservations, email Rachel at ilsthortsoc@gmail.com or call 217-853-6048.

- Southern Illinois Summer Twilight Series Meeting, June 15, 2015. 6:00 p.m. at Ridge Road Vineyard, 1653 Ridge Road, Pulaski, IL 62976. Program is free but pre-registration is required by Friday, May 15, at https://web.extension.illinois.edu/registration/?RegistrationID=12224 or by phone at 618-382-2662. For more information, check the link provided or contact: Bronwyn Aly at baly@illinois.edu or 618-382-2662 or Nathan Johanning at njohann@illinois.edu or 618-687-1727.

Regional Reports

From southern Illinois ... We have been dodging showers for about a week, and as soon as it starts to get nice and dry we get another shower again. Unfortunately, this has created challenges for field work and keeping up with cover sprays on tree fruits. Cloudy, damp days have not been ideal for our strawberry crop and instead have contributed to fruit and root rots. Our forecast for the week has chances of rain almost every day, so hopes of a shift in the weather pattern might have to wait until at least the weekend. Temperatures last week were very cold, with lows in the 40s and highs struggling to get into the 70s a couple days. The cool temperatures slowed growth of warm season vegetables. Despite the rain in the forecast, this week's highs are predicted to be in the 80s. Maybe this was our blackberry winter and now we will be off to more consistent, warmer temperatures.

We are in the midst of the emergence of 13-year cicadas, and the woods are loud with the buzz of cicadas here in the Murphysboro area. Cicadas use young fruit trees for egg-laying, so protecting young scaffold limbs and branches is important. See the notes in the Fruit section below for more details.

Thanks all who made it out to our first of the season Southern Illinois Summer Twilight Meeting at Miller Farms in Campbell Hill on May 18. We had around 75 people at this meeting where we discussed plasticulture strawberries, low tunnel tomatoes, cover crops, blueberry production, and spotted wing Drosophila. Also, a special thank you to John Miller and family for hosting the meeting! Check the program listings above for information of our next twilight meeting at Ridge Road Vineyard in June and other upcoming programs and field days.

May 18 Twilight meeting at Miller Farms, Campbell Hill.

Nathan Johanning (618-939-3434; njohann@illinois.edu) and Bronwyn Aly (618-382-2662; baly@illinois.edu)

From western Illinois ... Recent rains have created some difficulties with field work and harvest. After going most of the spring with scant precipitation, I've received almost 4.5" of rain the past three weeks at Quincy. Needless to say, the last few rains have really hampered any efforts to get field work completed. Succession plantings and harvest of strawberries are both becoming difficult, and rain is forecast throughout the week. Of course, the good news is that irrigation sure isn't necessary at this time.

I've seen and heard of several instances of 2, 4-D drift on crops such as grapes and tomatoes. These two crops are extremely susceptible to the phenoxy herbicides (2, 4-D and dicamba). Many drift injuries associated with these crops and these herbicides are vapor drift, not particle drift. These two herbicides can volatilize and move as a vapor up to three days after application and travel in whatever direction the winds blow. Movement up to one mile has been noted. Temperatures above 80 degrees are critical for vapor formation. Our area had several instances over the past few weeks when temperatures were above these thresholds. Injury symptoms will appear on the newest growth, as these herbicides translocate within the plant. Affected tissue shows malformed and twisted growth – epinastic growth.

Affected plants must metabolize the herbicide before normal growth can occur. In some instances, this may not occur during the current growing season. There is no good way to determine how long affected plants will suffer. Observe new growth for symptoms (or lack thereof). In severe cases, symptoms can be observed for a period of up to several years in perennial crops.

Phenoxy herbicide injury to grape (left) and tomato (right).

Anthracnose of strawberry.

Anthracnose of strawberry has also been noted of late. This has coincided with warmer temperatures and accompanying rainfall. Anthracnose lesions on strawberry fruit appear as dark necrotic spots and can be most easily found on older strawberry plantings where inoculum can build over the years. The pathogen is most active at higher temperatures and requires 100% humidity. Control via application of fungicides can be partially effective, but application must start prior to symptom development. For fungicide recommendations, see the 2015 Midwest Small Fruit and Grape Spray Guide.

With all the rainfall, botrytis rot has also been noted in some strawberry plantings. Advanced symptoms on strawberry appear as fuzzy gray masses on fruit. Dead strawberry leaves are the primary source of inoculum and the reason why removing dead leaves off of plasticulture plants is necessary. Optimal conditions for spread of botrytis are temperatures in the range of 60-65 degrees and high humidity or leaf wetness. Fungicide application during bloom is an important tool to help provide control of this disease, as conditions for infection have been favorable during the first several days of bloom.

High-tunnel strawberry harvest has essentially concluded here. Plasticulture harvest is ongoing, and matted row early varieties are just beginning to mature. A few grape flowers are visible. In Calhoun County last week, early-maturing blueberries were starting to turn color. Peaches and apples are sizing rapidly, and thinning will be required in most all plantings in this area. Blackberry bloom is in late stages, with some small fruit visible.

Between rains, planting and setting of transplants is ongoing where conditions allow. Cole crops are advancing, with broccoli heads ranging up to 6 inches in diameter. Very little noticeable "worm" injury has been seen in untreated cole crops so far. Early potato harvest has begun, and some early peas were available at the most recent local farmers' market. Asparagus harvest has ended or will soon. Suckering and trellising of determinate tomatoes has been ongoing.

Mike Roegge (217-223-8380; roeggem@illinois.edu)

Transitions ... A note on our University of Illinois Extension staff of Local Food Systems and Small Farms educators: Kyle Cecil, Extension Educator for Henderson, Knox, McDonough, and Warren counties, will leave University of Illinois Extension at the end of May. Kyle is taking a position as Dean of Carl Sandburg College in Galesburg. We're sorry to see him leave Extension but wish him well.

Fruit Production and Pest Management

Periodical Cicadas in Southern Illinois

Periodical cicadas in southern Illinois.

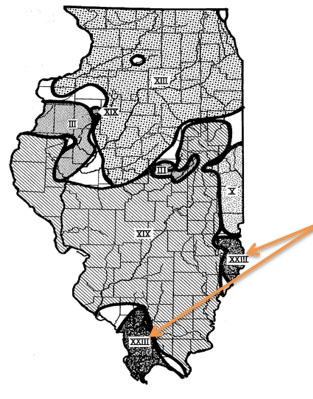

In the March 5, 2015, issue of this newsletter, I noted that Marlatt's Brood XXIII 13-year periodical cicada would emerge in the lower Mississippi River Valley this spring. This brood contains all four described species of periodical cicadas – Magicicada neotredecim, Magicicada tredecim, M. tredecassini, and M. tredecula. Nathan Johanning reported that these cicadas are now numerous in the south, so here's a repeat of some text adapted from the 2015 Midwest Tree Fruit Spray Guide.

Periodical cicadas are orange and black, about 1 ½ inches long, with mostly transparent wings; they appear mainly in late May and June. Annual or dog-day cicadas are larger, mostly green and black, and appear each year from July to September. Ordinarily, annual cicadas do not cause much damage. Cicada males announce their presence to the voiceless females by making a continuous, high-pitched shrill sound. The adult females lay eggs in rows in pockets that they cut in small branches and twigs of trees with their long, knife-like egg-laying organ. The eggs hatch in 6-7 weeks, and the newly hatched nymphs fall to the ground and burrow until they find suitable roots, usually 1 ½ to 2 feet beneath the soil surface. With their sucking mouthparts, they immediately begin to suck juices from the roots. Females prefer oak, hickory, apple, peach, and pear trees and grape vines for laying eggs. Because the numbers of periodical cicadas are so great during emergence years, egg-laying by females can severely damage twigs and small branches of fruit trees (and other trees), brambles, blueberries, and grapes. Damage occurs when the females make slits in branches and twigs in which to deposit the eggs. These small twigs and branches turn brown and die, sometimes breaking off. The damage may be severe in newly planted orchards. Egg-laying damage can be prevented on small trees by covering the tree with protective netting, such as cheesecloth. Cover the tree and tie the netting to the trunk below the lower branches, then remove the covering when egg-laying is over. If netting is not a practical option, you may apply insecticides when egg-laying begins and repeat as necessary when reinfestations occur. Pyrethroids are generally most effective insecticides against periodical cicada, but they may also trigger mite outbreaks because they kill the predators that help to keep European red mite in check. Pyrethroids registered on one or more perennial fruit crop include Asana, Baythroid, Brigade, Danitol, Mustang Max, Pounce, and Warrior. All of these insecticides are classified for restricted-use, so only licensed pesticide applicators are allowed to purchase them. Check the 2015 Midwest Tree Fruit Spray Guide to see which insecticides are labeled for use on which crops.

|

Older maps of Marlatt’s Brood XXIII indicate its distribution as shown to the left. For a more recent map of its distribution and some comments, see http://www.magicicada.org/about/brood_pages/broodXXIII.php. |

Corn Earworm in Strawberries

Corn earworm larvae and damage to strawberries (photos by Rick Weinzierl and Nathan Johanning).

In the May 12 issue of this newsletter I noted that our traps at Urbana were capturing corn earworm moths – an unusually early observation of flight. Rick Foster at Purdue in Indiana also has recorded early captures of corn earworm moths, and it appears that this early migratory flight has occurred elsewhere in Illinois as well, as strawberries infested with and damaged by corn earworms were collected in a plasticulture planting in southern Illinois early last week. Only a very few berries were infested, but this occurrence illustrates that corn earworm / tomato fruitworm has a wide host range and feeds on fruits of many crops. I don't think that most strawberry plantings will need to be treated to control earworms, but if control is necessary, Brigade (0), Coragen (1), Entrust (1), and Radiant (1) are labeled for use on strawberries and should be effective. Numbers in parentheses indicate the preharvest interval or PHI (time that must elapse between application and harvest) for each product in strawberries; Entrust is approved for use in organic production.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Potato Leafhopper on Apples

Left to right: cupping of apple leaves as a result of potato leafhopper feeding, potato leafhopper nymph, and adult.

No reports yet, but ... this is the time of the season when potato leafhoppers migrate into Illinois from the south on weather fronts. They feed on a wide range of fruit, vegetable, field crop, and landscape plants by inserting their needle-like mouthparts (stylets) into leaves and shoots, then sucking out plant fluids. In the process, they inject a salivary toxin into the leaves or shoots, causing a variety of symptoms, all of which are sometimes referred to as hopper burn. In apples, potato leafhopper feeding causes cupping of new leaves and greatly reduced growth of new shoots. In most years, potato leafhopper damage is most common in young trees that are not yet bearing fruit, as growers are not spraying them regularly for other insect pests (and coincidentally killing potato leafhopper). In addition, the switch from organophosphates such as Imidan and Guthion to alternatives such as Altacor, Rimon, and Delegate for codling moth control in apples allows potato leafhopper infestations to develop in fruit-bearing blocks, because these insecticides do not control potato leafhoppers.

Sample for potato leafhoppers by examining the undersides of leaves. Look for light-green, narrow, small (< 1/8 inch long) insects that tend to move sideways (instead of forward or backward) when disturbed. Thresholds suggested for potato leafhopper control range from treating whenever adults and nymphs are found on young trees to 1 adult or nymph per leaf on older trees where vigorous new growth is less important. Unlike white apple leafhopper (which is resistant to several insecticides), potato leafhopper is susceptible to most of the broad-spectrum insecticides used in apples –Imidan, neonicotinoids such as Assail and Calypso, pyrethroids such as Danitol (and others), and carbamates such as Lannate and Sevin. Again, Altacor, Belt, Delegate, and Rimon do not control potato leafhopper.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Notes on Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Codling Moth and Oriental Fruit Moth

During peach thinning last week at the U of I Fruit Research Farm at Urbana, we found a just-starting-to-hatch egg mass of brown marmorated stink bug. This insect has been the topic of lots of discussions over the last few years. For more background information, see http://ento.psu.edu/extension/factsheets/brown-marmorated-stink-bug, http://plant-pest-advisory.rutgers.edu/bmsb-insecticide-options-revised/bmsb-spray-schedule-table-3/, and http://jhawkins54.typepad.com/files/insect_management_updates_for_apples_peaches_brambles-weinzlerl.pdf.

Brown marmorated stink bug egg mass and newly-hatched nymphs.

For a few fruit crops that are highly susceptible to damage by brown marmorated stink bug feeding, the table below lists a few of the insecticides most likely to provide effective control. See http://plant-pest-advisory.rutgers.edu/bmsb-insecticide-options-revised/bmsb-spray-schedule-table-3/ for a more extensive listing.

|

Preharvest Interval (days) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Apples |

Peaches |

Brambles |

Actara (thiamethoxam) |

14 |

14 |

3 |

Belay (clothianidin) |

7 |

21 |

Not Registered |

Brigade (bifenthrin) |

Not Registered |

Not Registered |

3 |

Danitol (fenpropathrin) |

14 |

3 |

3 |

Lannate (methomyl) |

14 |

14 |

Not Registered |

Mustang Max (zeta-cypermethrin) |

14 |

14 |

1 |

Codling moth flight at Urbana began on May 5, and through May 26, degree-day accumulations (base 50F) totaled 367. Based on published phenology models, first generation codling moth flight is estimated to be about 70 percent complete here, and roughly 20 percent of first generation eggs are estimated to have hatched.

Oriental fruit moth flight at Urbana began on April 18, and through May 26, degree-day accumulations (base 45F) totaled 648. Most first-generation larvae enter the tips of new shoots in peaches and cause flagging. Second-generation moth flight begins approximately 900 base 45 degree-days after the biofix for first generation (beginning of first generation flight). We are likely to reach 900 degree-days here by around June 7. Larvae that hatch from eggs laid by second-generation moths typically enter fruits of peaches and render the fruit unmarketable.

Oriental fruit moth damage to peach shoots.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Vegetable Production and Pest Management

Corn earworm / Tomato Fruitworm

Our corn earworm traps at Urbana have continued to catch 5-10 moths per trap per night over the last several days. It appears that this early migration from the south has occurred in other areas of Illinois and Indiana as well. As I noted in the May 12 issue of this newsletter, tomatoes and peppers in high tunnels and any very early outdoor tomatoes in southern Illinois are vulnerable to infestation.

Potato Leafhopper on Green Beans and Potatoes

As noted above under the Fruit heading, now is the time to expect potato leafhopper immigration from the south on weather fronts. In Illinois vegetable crops, potato leafhopper is particularly damaging to potatoes and green beans. As it feeds by inserting its stylet into leaves and sucking out plant fluids, it also injects its saliva into the plant. The saliva is toxic to plants, and leaves typically yellow and curl and plant growth is stunted. See the 2015 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide at https://btny.purdue.edu/Pubs/ID/ID-56/ID-56.pdf or https://btny.purdue.edu/Pubs/ID/ID-56/ for listings of insecticides registered for use against potato leafhopper on specific crops.

Potato leafhoppers and injury to potato and green bean leaves. (Photos, L to R, are from Michigan State University, Penn State University, and the University of Massachusetts.)

Spotted and Striped Cucumber Beetles

Spotted and striped cucumber beetles are active and feeding on cucurbits in much of the state. These cucumber beetles are vectors of the pathogen that causes bacterial wilt of cucumbers and muskmelons.

Spotted cucumber beetle (left) and striped cucumber beetle (right).

Spotted cucumber beetles always have 12 distinct spots on the wings. The front, center spots are distinct and do not form a triangle as they do on the bean leaf beetle. Striped cucumber beetles have distinct black stripes along the inner and outer edges of the wings, and the stripes run all the way to the ends of the wings. The underside of the abdomen is black. Both of these insects overwinter as adults and move into fields and gardens in April through May, as soon as temperatures warm up and their food plants become available. They lay eggs at the base of their host plants, and larvae develop below ground, feeding on the roots. One or two summer generations of adults emerge and feed, mate, and lay eggs; adults of the latter of these summer generations overwinter.

Using FarMore-treated seed or soil applications of Admire or Platinum provide 2-3 weeks of control via systemic movement of insecticide from soil or seed to foliage. To protect against movement of Admire or Platinum into pollen and nectar (and possible poisoning of bees), do not apply these products as drenches any later than at transplanting. Several insecticides, including pyrethroids and Sevin, are effective against cucumber beetles (see the 2015 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide). Data and recommendations on thresholds (infestation densities that warrant control) differ for crops that are susceptible to bacterial wilt (cucumbers and muskmelons) and those that are not. Control – to prevent transmission of bacterial wilt that kills plants – is also more important in areas where bacterial wilt was prevalent in the previous crop season. To protect against wilt in cucumbers and muskmelons, treating when populations reach 1 beetle per plant is recommended. See http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/publications/E-101.pdf for more info on scouting (including the use of yellow sticky traps) and control.

Rick Weinzierl (217-244-2126; weinzier@illinois.edu)

Less Seriously ...

... another favorite from the past. Bill Shoemaker provided this gem in 2003...

After every flight, pilots fill out a form called a gripe sheet, which conveys to the mechanics problems encountered with the aircraft during the flight that need repair or correction. The mechanics read and correct the problem, and then respond in writing on the lower half of the form, telling what remedial action was taken, and the pilot reviews the gripe sheets before the next flight. Never let it be said that ground crews and engineers lack a sense of humor. Here are some actual logged maintenance complaints and problems as submitted by Qantas pilots and the solution recorded by maintenance engineers. By the way, Qantas is the only major airline that has never had an accident.

(P = The problem logged by the pilot.)

(S = The solution and action taken by the engineers.)

P: Left inside main tire almost needs replacement.

S: Almost replaced left inside main tire.

P: Test flight OK, except auto-land very rough.

S: Auto-land not installed on this aircraft.

P: Something loose in cockpit.

S: Something tightened in cockpit.

P: Dead bugs on windshield.

S: Live bugs on back-order.

P: Autopilot in altitude-hold mode produces a 200 feet per minute descent.

S: Cannot reproduce problem on ground.

P: Evidence of leak on right main landing gear.

S: Evidence removed.

P: DME volume unbelievably loud.

S: DME volume set to more believable level.

P: Friction locks cause throttle levers to stick.

S: That's what they're there for.

P: IFF inoperative.

S: IFF always inoperative in OFF mode.

P: Suspected crack in windshield.

S: Suspect you're right.

P: Number 3 engine missing.

S: Engine found on right wing after brief search.

P: Aircraft handles funny.

S: Aircraft warned to straighten up, fly right, and be serious.

P: Target radar hums.

S: Reprogrammed target radar with lyrics.

P: Mouse in cockpit.

S: Cat installed.

P: Noise coming from under instrument panel. Sounds like a midget pounding on something with a hammer.

S: Took hammer away from midget.

University of Illinois Extension Specialists in Fruit and Vegetable Production & Pest Management

Extension Educators – Local Food Systems and Small Farms |

||

Bronwyn Aly, Gallatin, Hamilton, Hardin, Pope, Saline, and White counties |

618-382-2662 |

|

Katie Bell, Franklin, Jackson, Perry, Randolph, & Williamson counties |

618-687-1727 |

|

Sarah Farley, Lake & McHenry counties |

847-223-8627 |

|

Nick Frillman, Woodford, Livingston, & McLean counties |

309-663-8306 |

|

Laurie George, Bond, Clinton, Jefferson, Marion, & Washington counties |

618-548-1446 |

|

Zachary Grant, Cook County | 708-679-6889 | |

Doug Gucker, DeWitt, Macon, and Piatt counties |

217-877-6042 |

|

Erin Harper, Champaign, Ford, Iroquois, and Vermillion counties |

217-333-7672 |

|

Grace Margherio, Jackie Joyner-Kersee Center, St. Clair County |

217-244-3547 |

|

Grant McCarty, Jo Daviess, Stephenson, and Winnebago counties |

815-235-4125 |

|

Katie Parker, Adams, Brown, Hancock, Pike and Schuyler counties |

217-223-8380 |

|

Kathryn Pereira, Cook County |

773-233-2900 |

|

James Theuri, Grundy, Kankakee, and Will counties |

815-933-8337 |

|

Extension Educators – Horticulture |

||

Chris Enroth, Henderson, Knox, McDonough, and Warren counties |

309-837-3939 |

|

Richard Hentschel, DuPage, Kane, and Kendall counties |

630-584-6166 |

|

Andrew Holsinger, Christian, Jersey, Macoupin, & Montgomery counties |

217-532-3941 |

|

Extension Educators - Commercial Agriculture |

||

Elizabeth Wahle, Fruit & Vegetable Production |

618-344-4230 |

|

Nathan Johanning, Madison, Monroe & St. Clair counties |

618-939-3434 |

|

Campus-based Extension Specialists |

||

Kacie Athey, Entomology |

217-244-9916 |

|

Mohammad Babadoost, Plant Pathology |

217-333-1523 |

|